Our Virginia: 2022 Impact Report

From the Appalachians to our Atlantic barrier islands, we're seeing conservation pay off across Virginia.

From the Director

Conservation's New Frontier

Our Virginia mountains were once the American frontier. Indigenous peoples, of course, stewarded the Appalachians for millennia. But it wasn’t until the lead-up to the American Revolution that Daniel Boone set out from his home along Virginia’s Clinch River to begin opening the Wilderness Road into Kentucky.

In a sense, history has come full circle, as our Appalachian region is gaining recognition as a new frontier in conservation. This time, it’s global climate change rousing our revolutionary spirit. Such an all-encompassing threat requires us to declare independence from past thinking and to reimagine our strategies for conquering 21st century environmental challenges.

That’s why The Nature Conservancy ventured into uncharted territory in 2019 with our quarter-million-acre Cumberland Forest acquisition. TNC’s Virginia, Kentucky and Tennessee chapters; our NatureVest division; and outside impact investors forged a unique alliance to pursue a shared vision of positive change across this vast swath of Appalachia.

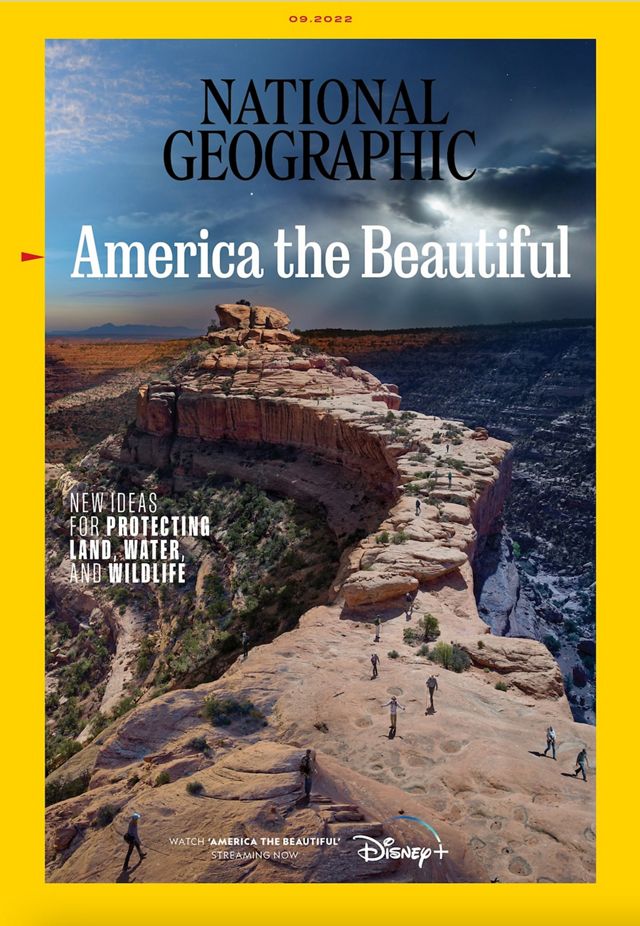

It’s extremely gratifying that, this fall, a National Geographic magazine cover story highlights Cumberland Forest as one of four projects representing the leading edge of conservation. As the article states, traditional conservation of preserves and public lands has produced extraordinary results. But in the face of climate change, conservation must engage everywhere.

Moreover, the article goes on to say, “You have to make conservation pay better than destruction.” We’re seeing this theory of change play out—and pay off—in the Cumberland Forest. We see it in the elk herd that’s thriving on former minelands. In our partnerships to generate solar energy from other minelands. And in the local community entrepreneurs whose nature-based ventures we’re supporting.

In fact, as the examples in this report show, we’re seeing conservation pay off across Virginia, from the Appalachians to our Atlantic barrier islands. Your support makes Virginia a conservation leader. We deeply appreciate your commitment to a brighter future for nature and people.

The Appalachians: Geography of Hope

A quarter of the famous 2,200-mile Appalachian Trail runs through Virginia—more than any other state. This foot path and the forested ridges, pastoral valleys and swift streams of the surrounding landscape are beloved for their scenic beauty and recreation opportunities. For The Nature Conservancy, these ancient mountains ranging from Alabama into Canada are a top conservation priority because of their resilience and diversity in the face of global climate change.

Unbridled Generosity: Hobby Horse Farm Elevates Mountain Conservation

A generous gift by Truman Semans of his family’s historic Hobby Horse Farm in western Virginia’s Bath County bolsters our adjoining Warm Springs Mountain Preserve as a flagship for Appalachian Mountains conservation.

“This farm is, for us, heaven on Earth,” says Semans. “We are proud to give it to The Nature Conservancy.”

TNC envisions this 600-acre slice of heaven eventually serving myriad purposes: regional hub for implementing climate-resilience solutions; training center for fire teams; housing for visiting scientists, students, legislators and environmental leaders; and model of effective conservation for the entire Appalachian range.

Strategically located in the Central Appalachians, Hobby Horse Farm nestles into our 9,000-acre preserve, which, in turn, shares a 13-mile boundary with the vast George Washington National Forest. It also fits perfectly into TNC’s short-term goal of protecting 3 million acres as a critical migration corridor for Appalachian wildlife responding to changes in climate.

Hobby Horse Farm and Warm Springs Mountain Preserve both owe much to the stewardship of the Ingalls family who, more than a century ago, purchased the mountain that rose over the fabled Homestead Resort. Smitten by the mountain’s beauty, they carved out their own oasis on its western shoulder.

This beautiful 600-acre property sits below and seamlessly fits into our Allegheny Highland Program’s Warm Springs Mountain Preserve. This gift will profoundly impact our work across the Appalachians and help us achieve our bold conservation vision in the decades to come.

Reimagining Conservation in the Cumberland Forest

“The [Cumberland Forest] property is a complex set of discontinuous parcels punctured by inholdings, an Appalachian lace. But it contains a variety of latitudes, altitudes and microclimates that offer options for the future—and enough continuity that animals can range freely. Among those animals is one long missing from these woods: elk.”

— Excerpt from National Geographic cover story, September 2022

National Geographic magazine’s September 2022 cover story profiled four sites across the United States representing the leading edge of conservation in the 21st century.

“To safeguard all our species, all our ecosystems—and to make sure that they have the resources and space to adapt as the climate continues to warm—we need to do conservation everywhere,” the article states.

In addition to traditional preserves and public lands, “everywhere” includes Appalachian communities and the working lands of TNC’s Cumberland Forest. Continued on-the-ground progress here depends on buy-in from outside impact investors and local communities alike.

Learn More: Explore the Cumberland Forest

Science Yields Seeds of Hope

Cool, moist air kisses your skin. The very ground beneath your feet feels less than solid; a squelch sound accompanies every step, as spongy soil grabs at your feet. The vibration you felt first in your chest soon fills the air, and you realize your heart is fine: there’s a ruffed grouse nearby drumming its wings.

“It’s really a magical feeling,” says Kathryn Barlow, restoration manager for TNC’s Central Appalachian Program. Barlow is describing the experience of walking into an Appalachian red spruce forest, especially on a summer day.

Unfortunately, these iconic forests attracted the timber industry during a time when forestry was far from sustainable. By the 1930s, a mere 10% remained. Over the last 20 years, TNC has worked to overcome two related challenges to restoration: mature red spruce forests are scarce and fragmented, and this isolation has resulted in trees with unnaturally low genetic diversity.

Today, there’s new hope thanks to TNC’s teaming up with the University of Vermont and contractor Dave Saville, a founder of the Central Appalachians Spruce Restoration Initiative. Seeds are collected from areas ranking high in genetic diversity. Saville then works with nurseries to grow seedlings—about half a million just last year.

“This effort has been an incredible example of how to connect science and practice to advance conservation,” Barlow says. Specifically, greater genetic diversity means a healthier forest—and that’s a doubly important advance in the face of climate change.

Learn More: Explore 20 years of red spruce restoration.

Fire: Burning to Learn at Virginia WTREX

In Spring 2022, a pandemic-delayed gathering of wildland fire professionals finally took place at The Nature Conservancy’s Piney Grove Preserve. Some participants traveled long distances, crossing a continent or an ocean. Others undertook different journeys, overcoming myriad life and career challenges.

At least 90% of the participants were women. Look at virtually any fire crew across the country and you’ll see the reverse. In fact, many of these women have experienced being the only woman working with an otherwise all-male team.

Quote: Jennifer Morris

As I took part in the training and deep discussions about equity and inclusion, I was awestruck by the women that stand shoulder to shoulder in this field.

Spanning two weeks of intensive workshop and field experiences, the 2022 Women-in-Fire Training Exchange (or WTREX) aimed to support and retain the women working on fire lines in Virginia and around the world.

WTREX is the brainchild of the six women who participated in a standard Prescribed Fire Training Exchange in 2015. Among the founders were Nikole Simmons, from TNC in Virginia, and Colorado firefighter Monique “Mo” Hein, an incident commander overseeing WTREX’s controlled burns. The group concluded that a female-focused event would create a safe, supportive environment to accelerate learning.

Quote: Monique “Mo” Hein

Most of us were used to working in an environment where we were the only female on our crew. We started to talk about how to make things better, not just for us but all women in fire.

WTREX has exceeded expectations, and demand now far exceeds supply. Being accepted for one of WTREX’s limited slots meant new challenges for South Africa’s Kylie Paul, who was determined to make her way to Virginia. “I quit my job, I packed up my house, and a bunch of folks got behind me and helped me to raise money to be here,” she says. “TNC’s been amazing, helping me with travel costs and accommodations.”

While limited funding remains a challenge, organizers are optimistic that WTREX can grow to accommodate more women—and potentially other underrepresented groups—to foster diversity and strengthen the global wildland workforce.

For now—coincidentally, the 60th anniversary of TNC’s “Good Fire” programs—our organization’s investment in fire and in women resonates especially strongly among relative newcomers to fire work. This group has been prone to leave and pursue other careers.

Learn More: More more of the trailblazing women in fire.

Quote: Zoe McGee

WTREX is physically, mentally and emotionally exhausting, but it was totally worth it. It was such a powerful experience, and we’ve built a community and network that we will have for years to come.

2022 Highlights

Year in Photos

From celebrating 50 years of conservation on the Eastern Shore with our staff at the Volgenau Virginia Coast Reserve (VVCR) to setting new records for shellfish restoration, we’ve marked some major milestones in 2022.

Support Our Work in Virginia

Signs of Elk: The Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources and local partners helped TNC install new interpretive signs focused on elk restoration and the surrounding Cumberland Forest. © Nick Proctor / TNC

Raising the Reef: The Virginia Marine Resources Commission, a TNC partner in large-scale oyster restoration, recently constructed 150+ acres of new reef in the lower York River. © Andy Lacatell / TNC

Red Fox in Snow: Taken in my yard in Springfield, Virginia this Red Fox appears to be fascinated with the snow and looks like he is trying to catch a snowflake. © Charles Schmidt/TNC Photo Contest 2022

Generational Impact: Virginia hosted a celebration of TNC's 50th anniversary on the Eastern Shore and was able to thank the Volgenau family in person for their decades of support. © Bill Kittrell / TNC

Approach the Bench: TNC’s stewardship team and volunteers work hard to maintain preserve trails, including mowing this footpath on Warm Springs Mountain Preserve. © Josh Mitri / TNC

Roaring Springs Preserve

Under the Milky Way

Roaring Springs Preserve, donated to TNC by Fitz Gary, fits into a mosaic of conservation lands stretching from Highland County into West Virginia’s Monongahela National Forest. Astrophotographer Brennan Gilmore describes the experience of visiting this dark-sky area, ideal for stargazing, and capturing this image.

For hours I familiarized myself with the property, parting the grass seas, climbing the steep valley walls, and wading up to my waist in muddy water. Somehow I managed to get down the valley to the field of boneset and ironweed flowers I had identified earlier in the day as my primary shooting location. Once in place, I shot for nearly an hour. While the camera took five-minute exposures, I lay on the ground, staring up at the heavens and listening to beavers swim and slap the water in the nearby pond. They certainly seemed as happy as I was to be there.

2022 By the Numbers

-

500K

Acres that The Nature Conservancy has protected across the commonwealth of Virginia.

-

253K

Across the three states being managed under TNC's Cumberland Forest Project.

-

121K

Acres of public land across Virginia that TNC has worked with partners to protect.

Lands and Lives: Interns Help Broaden Support for Conservation

Three summer interns—undergraduate Basia Scott, recent graduate Vanessa Moses and graduate student Claudia Moncada—helped The Nature Conservancy expand our outreach to underserved communities and enrich our interpretation of the places we protect. Meet our interns and hear directly from them about their projects.

Learn More: Explore our interns' work in depth and read more about their experiences and plans for the future.

Lands and Lives Intern, Statewide

Basia Scott

I absolutely love history and telling stories, specifically those of the underrepresented. So having a chance to focus on lands and lives, exploring stories and conditions through the lens of place, was incredibly interesting to me. I had two major projects over the course of the summer. One was [documenting] the historical Indigenous presence in the places that TNC protects within Virginia.

I am also working on an article that explores the complex relationship that the African American community has with nature—and misunderstandings of that relationship. Often, it seems that people both outside and inside the community feel that nature (and therefore conservation) is not for Black Americans, but through the examination of our past, we can find quite quickly that nature has been an underlying part of oppression and freedom, serving as a canvas for our story.

My highlight was getting to visit the Eastern Shore of Virginia—an amazing opportunity to meet other interns, get closer with my team, and learn more about the historical contexts of the Brownsville Preserve.

Spanish Language Conservation Outreach, Eastern Shore

Claudia Moncada

Science communication, and specifically bilingual science communication, is very important to me. The big community engagement event I planned was for Latino Conservation Week, a nationwide event from the Hispanic Access Foundation that aims to get more Latino and Spanish-speaking people out in nature. We held a picnic lunch and bilingual wagon rides on July 23 at Brownsville Preserve and just encouraged people to come out to the trail with their families and enjoy nature.

So many people out there would greatly benefit from learning about the work TNC is doing and simply being outdoors and enjoying nature. But a huge portion of them is being missed due to things like language barriers. Since TNC is a global organization, I think it’s a natural next step to consider communicating its work beyond the people they have historically been reaching.

In making an effort to meet community members where they are, I think more people will be able to decide for themselves what they would like nature and conservation to mean, and that’s a choice that everyone deserves to be able to make.

Brownsville Preserve History, Eastern Shore

Vanessa J. Moses

This historical research included both of my passions, environmental stewardship and diversifying the conservation world. It also was an opportunity to understand and contextualize my own family history, as I have ancestors that have been on the Eastern Shore since the early 1800s.

My role is to uncover the overlooked history of enslaved and freed African American individuals who were members of the Brownsville and Nassawadox communities. Some may view Brownsville as just a historic site, but it was more than just a home. It was a plantation owned by the Upshur family, and, as such, it has a complicated and difficult history of enslavement and inequity built into its foundation.

It is my responsibility to fill in the gaps of knowledge about the first stewards of this land: the enslaved laborers and their descendants. I have created a family tree of approximately 80 enslaved people living in Brownsville between 1782 and 1855.

This internship has shown me that there are people-focused careers in conservation, and it has strengthened my resolve to diversify this field.

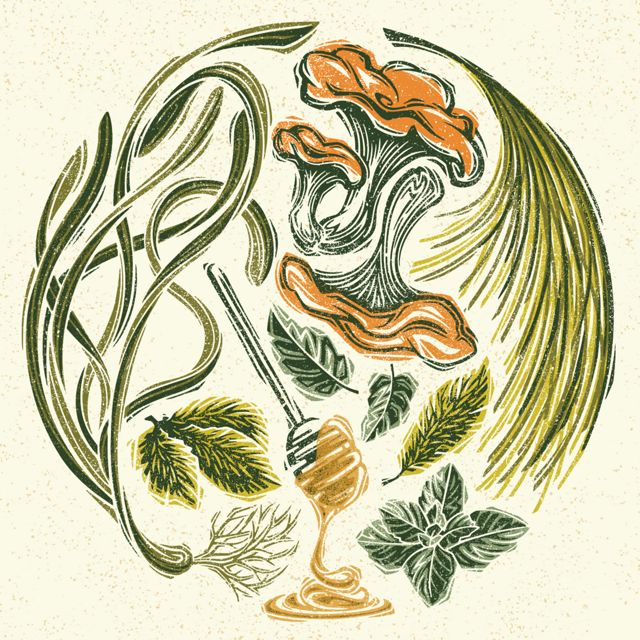

OktoberForest: Celebrating the Lands and Waters on Which all Life (and Beers) Depend

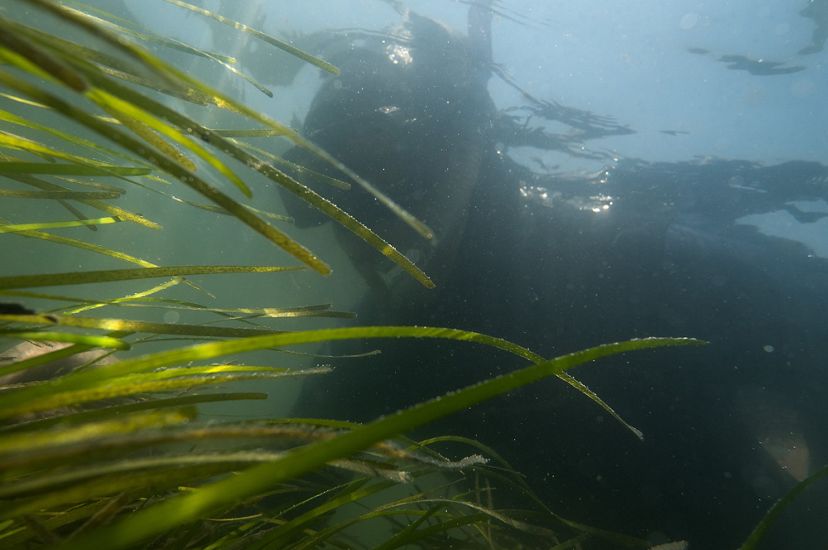

Foraging chanterelle mushrooms under the canopy of a mountain forest. Clipping red spruce tips after a hike up a steep ridge. Scooping seagrass from the deck of a skiff. No, these aren’t scenes from Gordon Ramsey: Uncharted. Nor is it how craft brewers typically procure ingredients.

OktoberForest Fest 2022, the brainchild of Black Narrows Brewing co-owner Josh Chapman, built on Chapman’s previous crazy idea (his words) to brew an India pale ale featuring longleaf pine from The Nature Conservancy’s Piney Grove Preserve. Kicking things up a notch, this year’s collaboration paired three additional breweries with TNC programs from the Atlantic to the Appalachians.

One wild local ingredient, carefully collected by hand, offers an expression of each area’s lands and waters that you can literally taste. On October 1, Black Narrows and TNC hosted a micro-festival in Chincoteague, where each brewery debuted its concoction and TNC staff shared the conservation story behind the brew.

Learn More: Get a taste of Virginia and explore the stories and videos behind the brews.

Quote: Brian Mandeville

The deeply passionate people doing the work of habitat restoration in these mountain forests were kind enough to share this magnificent space with our team, and we are excited to share an element of that mountain in this beer.

Quote: Josh Kauffman

Snorkeling the thriving young eelgrass beds, finding a few rare bay scallops and even (carefully) walking a razor-sharp intertidal oyster reef profoundly strengthened our appreciation for these sensitive ecosystems.

Quote: McKinnen Leonard

Collaborations like these bring such a meaningful purpose to our industry and help connect us.

Quote: Josh Chapman

We all gathered needles, branches and cones after an incredible tour of Piney Grove. I was blown away by the passion of the team behind the longleaf restoration.

Nature's Helpers: Virginia Volunteers Making a World of Difference

The Nature Conservancy’s volunteer programs in Virginia continue to rebound from pandemic impacts in a big way. Volunteer program manager Jennifer Dalke, who leads recruitment and compiles results, shared the following success stories from this year’s largest events.

Clean the Bay Day

In partnership with Fairfax County Parks, TNC recruited well over 500 volunteers for cleanups at 22 different sites. Volunteers donated almost 1,200 hours of labor and removed about 5.5 tons of trash from the Chesapeake Bay watershed.

City Nature Challenge

TNC hosted spring citizen-science events on the Eastern Shore and in Charlottesville, with 240 combined participants recording almost 2,500 observations of plants and animals.

Eastern Shore Seagrass Restoration

The world’s largest seagrass restoration project continues to grow. About 80 volunteers joined TNC staff and partners in late spring to harvest seed-bearing eelgrass shoots from coastal bays. Seeds will be extracted for replanting this fall.

Learn More: Discover how you can volunteer and connect with nature.

Volunteer Spotlight

My Snorkeling Adventure

11-year-old Kai shares his experience as an eelgrass volunteer.

We drove an hour and a half north up to the Eastern Shore to a remote area. Once we got there we suited up in wetsuits and got on one of two boats. On the way out there, we got a class on eelgrass and the history of the estuary.

The water was above my knees, almost to my waist. Nice shallow waters with many creatures to be found. It was very calm. Floating through the shallow water above the eelgrass was such a peaceful and calm place with all kinds of sea life. I found knobbed whelks, silverside fish and small mud crabs, four live whelks and a few hermit crabs.

I also found a toadfish hiding inside a whelk shell and a bunch of scallops—did you know that if you take a scallop out of the water for a bit, it slowly opens its mouth and then snaps shut! I also learned the little blue dots around the rim of their shell are actually eyes and that they can push themselves through the water with their ductor muscle.

It’s a simple task to pick out the seeds from the flat grass, but I did get majorly distracted by the sea life!

This experience was awesome. It was like swimming through an abyss of underwater grasses with sea life everywhere you look. Sometimes you find yourself so focused that you forget about the outside world or even what you are supposed to be doing. Time flew by very fast even though this journey was only a few hours long.

The group collected a total of 25 bags of eelgrass seeds, which were dumped into big tanks where they combined them with collections from previous days. I learned that the seeds will pop out of the shoots and the grasses will decompose.

As it decomposes, the oxygen gets used up, but the seeds do better with oxygen, so they stir the tanks every day. By early July the seeds are all popped out, so they skim the leftover grasses off the top, and the seeds drop to the bottom. They will move the seeds to smaller tanks, where they control the temperature so they don’t sprout yet. In October they will throw the seeds out in the areas that need more eelgrasses and then check back in March and hope it grew!

Everyone can do something every day to help the environment. It can be as easy as picking up trash and not littering. But if you can volunteer, it is a good way to meet people while having fun, learning something new and making a difference. This was a really awesome experience, and if you go, I hope you will enjoy it too!

Download the Report

-

Our Virginia: 2022 Impact Report

From the Appalachians to our Atlantic barrier islands, we're seeing conservation pay off across Virginia. Take a deep dive with our 2022 Impact Report.

DOWNLOAD

Descargar el Informe en Español

-

Nuestra Virginia: Informe de Impacto 2022

The Nature Conservancy en Virginia está trabajando por un futuro donde las personas y la naturaleza pueden prosperar. Obtenga más información en nuestra El Informe de Impacto Anual de 2022, ahora disponible en Español.

DOWNLOAD

We Can’t Save Nature Without You

Sign up to receive monthly conservation news and updates from Virginia. Get a preview of Virginia's Nature News email

Make a Difference

Together we can find creative solutions to tackle our most complex conservation challenges and build a stronger future for people and nature. Will you help us continue this work?