Sinking Cemetery: Salt Marsh and Sea Level Rise

Sea level rise in places like Taylors Island is impacting vulnerable Eastern Shore communities—and their history.

John and Sarah Robson sat stoically on the front seat of their stagecoach listening to the rhythmic sound of the horses’ footfalls on the dirt road. It was daybreak and the birds were busy. Bald eagles, osprey and marsh hawks were hunting while warblers sang from the branches of trees. It was a beautiful spring morning on the Eastern Shore of Maryland.

The young couple were headed West on an adventure to start their married lives together. It was shortly after the turn of the 19th century, and John—like many in his time—felt that it was his duty as a citizen of the new United States to spread his religious, political and social influence West into the uncharted wilderness. To John, it was a tremendous opportunity. It was his manifest destiny.

As John and Sarah turned out of the driveway and onto the road toward town, they took stock of all things they were leaving behind: the fields and pastures, the animals, the salty air, the old farmhouse that John’s grandfather Joseph had built half a century earlier (most likely with enslaved labor) and, a short distance from the farmhouse, the family cemetery where three generations of John’s kin were buried.

In 1977, more than 150 years after John and Sarah settled in Kentucky, The Nature Conservancy acquired the former Robson family farm. The land was donated by Frank M. Ewing, a Maryland lumber magnate, who had been cultivating the land as a tree farm.

Today, the Frank M. Ewing Robinson Neck Preserve is of extraordinary ecological value, providing habitat for wintering and nesting waterfowl, spawning fish and Delmarva fox squirrels. The preserve is also a popular recreational destination for nature lovers who enjoy birdwatching, hiking and the undisturbed beauty of a Chesapeake Bay saltmarsh.

The Robinson Neck Preserve is located on Taylors Island in Dorchester County, less than a mile from the open waters of the Chesapeake Bay. When it comes to vulnerability to sea level rise, Dorchester County is ground zero.

Current scientific models show that Dorchester, now the 4th largest county in the state of Maryland by land area, will become the 14th largest county by 2100 as thousands of acres of land convert to open water. Much of TNC’s Robinson Neck Preserve will be lost well before then, including the Robson family burial plot.

The Robson cemetery site was first identified by the preserve’s neighbor, Robert (Bob) Kirkley, a retired Methodist pastor and volunteer monitor for TNC’s Robinson Neck Preserve. Since 1984, Bob has been helping TNC with various monitoring and maintenance activities such as keeping the hiking trails mowed and accessible.

One day in the late 1990s, while walking the preserve, Bob came across a cluster of headstones located on the relatively high, wooded ground between two wide expanses of marsh.

Quote: Bob Kirkley

“The truth of the matter is, across the Eastern Shore, you’ll find graves wherever you are that people have lived.”

Life in a Salt Marsh

Salt marshes are some of the most unique and biodiverse habitats in the country. All around the Chesapeake and coastal bays, these brackish wetlands occupy that small sliver of space where tidal saltwater mixes with freshwater that drains from the land. North America is home to the majority of our planet’s tidal salt marsh vertebrates, so conserving these habitats is our national responsibility.

Tidal marsh bird populations serve as a primary indicator of marsh health and biodiversity as a whole because birds are easy to identify and are commonly studied. The Saltmarsh Habitat & Avian Research Program (SHARP) is a group of academic, governmental and non-profit collaborators gathering the information necessary to conserve tidal-marsh birds from Virginia to Canada.

Dave Curson, director of bird conservation for Audubon Maryland-DC, led the team that collected the baseline bird data for the marshes in the Chesapeake Bay and mid-Atlantic coastal bays on behalf of the SHARP collaborative. A SHARP paper published in 2019 describes the state of our mid-Atlantic salt marshes:

Eastern tidal marshes support significant endemic vertebrate diversity within the high marsh zone some of which are already exhibiting precipitous population decline. Loss in the high marsh zone could have disastrous repercussions in the bird community in particular; several species of sparrow currently maintain much (if not the majority) of their global breeding range within the high marsh zone from Maine to Virginia. Ecological services including carbon sequestration, coastal buffering from extreme storm events, and coastal recreation opportunities will also be impacted by a shift in tidal marsh vegetation communities driven by changing sea levels (Correll et al., 2018).

Quote: Dave Curson

“We need to care about salt marsh birds not just for the sake of the birds, but because they’re an indicator of the health of the entire ecosystem."

The salt marsh is one of the more misunderstood of all coastal landscapes. Mud, biting insects and the odor of decomposing organic material tend to overshadow the salt marsh’s beauty, complexity and ecological value.

These ecosystems are not only a critical component of the Chesapeake Bay region’s food web, they can act as a first line of defense for our coastal communities. Salt marsh habitats act as a buffer against storm surge. They can actually help protect human communities and take some of the energy out of storm surges.

In short, these stunning landscapes help feed us, protect us and inspire us. We must work to ensure their persistence. The nature we depend on depends on us.

Helping Nature Adapt to Change

In 2012, Superstorm Sandy pummeled the East Coast of the U.S., causing more than $50 billion in damage. According to a study led by TNC with partners from the engineering and insurance sectors, marshes and wetlands along the East Coast prevented more than $625 million in property damage during Superstorm Sandy.

Wetlands are like natural sponges that absorb floodwaters during storm surges. They are also of enormous ecological value, providing habitat to countless species of flora and fauna. We call these habitats our “green suit of armor.”

Salt marshes and tidal wetlands like those at the Robinson Neck preserve are resilient and built to adapt. However, accelerating sea level rise is claiming coastal habitats at a faster rate than the marshes can accrue the sediment needed to keep pace with the rising waters.

In other, more developed areas, coastal habitats are losing ground to the coastal squeeze where they are trapped between rising seas and upland development. This prohibits the marshes from migrating to higher ground as they have evolved to do. The green suit of armor that protects us needs our help.

Each year, TNC protects thousands of acres of land on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, with a focus on what our science has identified as wetland adaptation areas. Land protection—the oldest tool in our toolbox—still plays an important role in our conservation strategy to facilitate marsh migration so that our green suit of armor can persist in the face of a changing climate and rising seas.

Sinking Infrastructure

Unfortunately, the sinking Robson family cemetery is not an anomaly on the Eastern Shore. Several historical cemeteries in low-lying communities across Delmarva face a similar fate, and cemeteries aren’t the only cultural and historical sites that will be lost.

Sea level rise in the Bay has already claimed churches, cemeteries, homes and businesses—and in cases like James Island, located just off the shore of Taylors Island where the Robinson Neck Preserve is located—entire communities have been lost. We have lost a total of 13 Bay islands that were once mapped on nautical charts.

On Maryland’s Eastern Shore, much like the rest of the coastal United States, sea level rise is disproportionately impacting low-income communities and communities of color. After the abolition of slavery in the late 1800s, African Americans were forced to settle in the low-lying marshy areas along the shores of the Chesapeake Bay. Today, these marginalized communities are less likely to have the resources and capacity to prepare for and recover from the more frequent storms and flooding that we are experiencing as a result of climate change.

The Maryland/DC chapter of The Nature Conservancy understands that the time to act is now.

We also understand that the issues faced by our vulnerable communities are complex and difficult to solve: taxpayer-funded property buyouts, community relocations, increasing infrastructure repairs and historic preservation—just to name a few.

We know that the solutions to these problems must start with dialogue. The diversity of opinions, interests and values of the people who are being affected creates sensitivities that can slow or halt progress toward the changes that must take place.

To overcome this specific challenge, we are building a coalition of county planners, emergency responders, community leaders and conservationists so that we can begin the tough conversations necessary to find solutions. Even though the direct impacts of climate change and sea level rise are not always apparent to the untrained eye, Maryland’s vulnerable communities are feeling the urgency.

Documenting a Sinking Cemetery

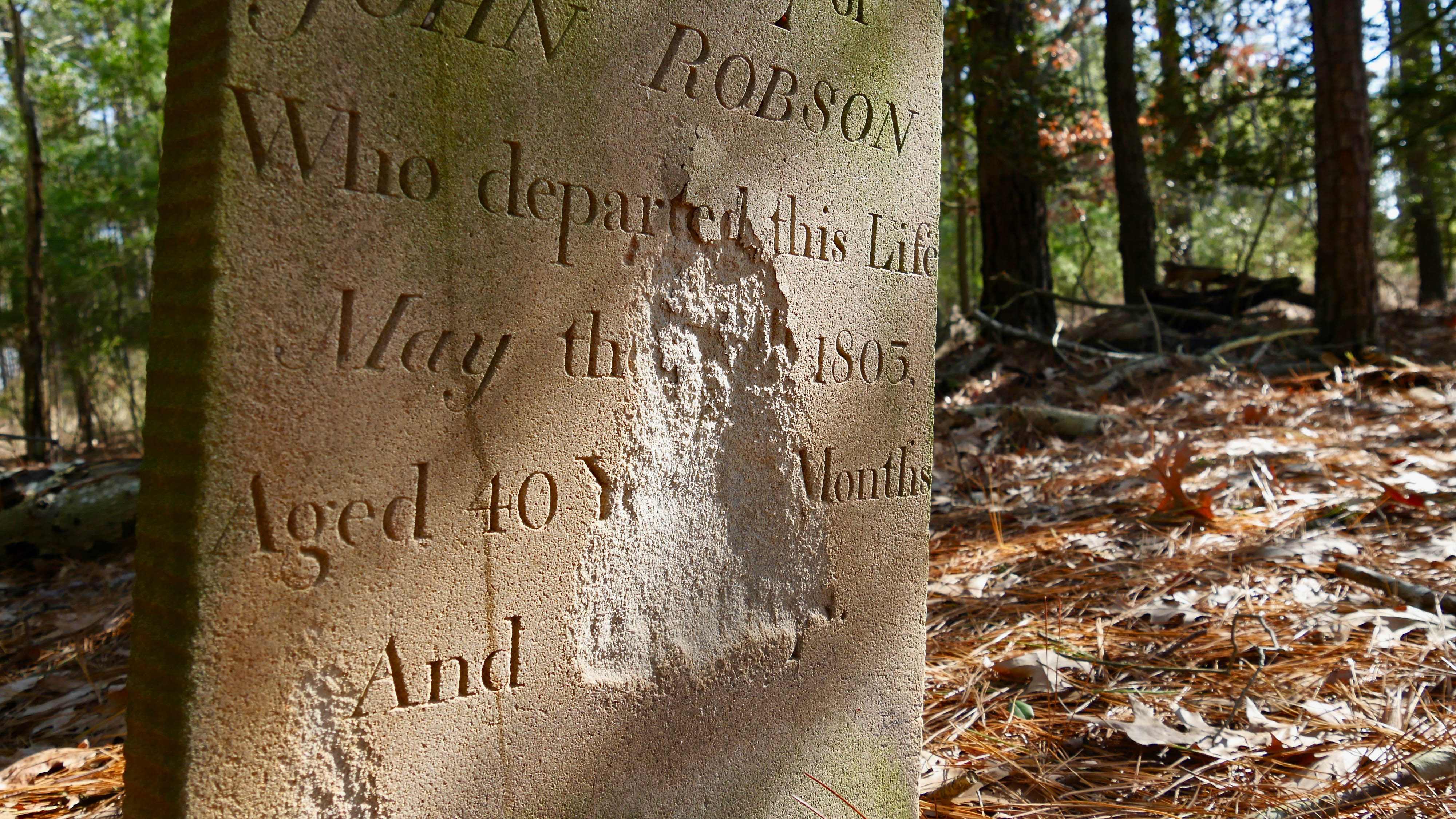

Many of the headstones in the Robson cemetery are cracked or broken from years of exposure to the elements and the salty bay air. Many have already sunk so deep into the ground that only the carved tops are left peeking out over the pine needles. On the intact headstones, the inscriptions are brief. As humble farmers, the Robsons weren’t inclined to embellish.

Quote

In memory of ANN MARIA ROBSON Who was born July 11th 1799

On a cold and clear February day, Joe Fehrer lies on his stomach and delicately sweeps away a pile of pine needles lying at the base of a half-sunken headstone so that he can read the last few lines of text. Joe is documenting the Robson family burial plot for the Maryland Historical Trust before the cemetery is lost to the rising waters of the Bay.

“This is going to be one of those places, that in the next 50 to 100 years, is going to be nearly unreachable by foot. So, before this site is lost, it’s our due diligence as landowners to document the site now so that future generations have access to the information. It’s our moral responsibility” says Joe.

After brushing away the pine needles, Joe squints to read the obscured text, then reads aloud, “In memory of Sarah Keene, who departed this life October 10th, 1851.” Then, looking up and smiling, Joe continues reading the final few lines he had just exposed, “who was a loving wife and mother.”

“What a wonderful tribute,” Joe concludes before transcribing the text into his field journal.

WATCH: Not wanting to see the site of the Robson family cemetery completely lost to history, retired TNC Project Manager Joe Fehrer documented the site for the MD Historical Trust.

We Can’t Save Nature Without You

Sign up to receive monthly conservation news and updates from Maryland/DC. Get a preview of Maryland/DC's Nature News email.