Who’s Best Qualified to Look After Our Natural Resources?

By Justin Adams, Executive Director, Tropical Forest Alliance

I recently flew over the Amazon rainforest from Marabá to São Felix do Xingu, heading southwest across Pará state. Looking down to the ground, I could see a clear divide.

On the right was the indigenous territory of the Xikrin, where the forest is lush and largely in tact. On the left the land was in private hands. While some scrappy clumps of forest remain, most is low productivity grazing land and, although green, it looks lifeless by comparison.

The boundary between the two is, quite literally, a line on the ground.

I’ve seen the same thing in the Mongolian grasslands. Travel to the far east of the country, where the borders of Mongolia, China and Russia all meet. Although they are under pressure from increasing herd sizes, the nomadic tribespeople are able to pursue traditional practices that emphasize collective stewardship of the lands. Over the border in both China and Russia, things are very different. From the air, you can see the land is obviously degraded and, again, there’s this clear, straight divide. (In fact, if you zoom right in on Google Earth, you can see it for yourself. You don’t need the line on the map to show you where the border is.)

These aren’t isolated examples. It’s a pattern we see over and over again. Where land is still managed by indigenous peoples, it does tend to be in remarkably good condition. And, as a consequence, you’re quickly led to the conclusion that indigenous peoples are the best guardians of our natural resources.

But we are talking about the environment here. As with most other environmental issues, it’s riven by deep differences of opinion. Is this correlation or causation? Is it simply because indigenous peoples lack the capacity for environmental degradation? Aren’t there plenty of exceptions? Isn’t this just dewy-eyed sentimentality?

These are valid questions. So, I’ve been determined to reach my own conclusions. I’ve read deeply on the subject. I’ve taken a particular interest in the long-established partnerships The Nature Conservancy (TNC) has with indigenous peoples and local communities, from Australia to Canada and from the Amazon to Africa. I’ve made a point to visit many of them for myself. And I’ve got a deepening conviction that these projects are among the most important work we do anywhere.

From these recent trips, I’d like to share some of my strongest impressions:

- Enduring, resilient and welcoming cultures - The resilience of indigenous peoples is remarkable. Despite 500 years of oppression, marginalisation and inter-generational trauma, many cultures remain intact. I’m therefore convinced they have valuable knowledge about thriving in the face of social and environmental adversity that the rest of us increasingly need.

- Benefiting from a deep sense of place - Although they live in vastly different geographies, the people I have met share some common values. You see a deep connection to place and a direct link between healthy lands and a healthy culture. It’s way beyond anything I have ever encountered in the west.

- Looking for collective approaches - I’ve been beguiled by the approach to open dialogue. In the west, I’ve witnessed increasing polarisation, stubbornly entrenched attitudes, and an inability to understand alternate perspectives. What I’ve noticed among indigenous communities is a positive outlook, a strong will to succeed, and also the grace to compromise.

- Combining new knowledge with traditional wisdom - We're not talking about turning back the clock or doing away with modern technology. On a recent trip to Australia, one of my fondest memories was watching Aboriginal Rangers, proudly “taking care of Country”, directing early-season burning activities, equipped with spreadsheets, tablet computers and the latest GPS devices. It was a thoroughly modern execution of an age-old practice.

It should surely go without saying that indigenous peoples are natural partners for conservation organisations like my own. But here’s pause for thought. The Guardian recently published an interview with Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous People. When asked about the biggest challenges facing today’s indigenous peoples, she said “I think the biggest threats are extractive industries, conservation projects and climate change.”

All too often, she says, “protected areas are still being established on indigenous lands without their consent, even though indigenous peoples are the proven best guardians of the forest and forcing them from their lands does not improve environmental outcomes.”

Think about that for a moment.

As environmentalists, we’re put in the exact same category as the extractive industry.

Quote

We have the opportunity to blend traditional knowledge and science with western knowledge and science.

The starting point is for environmental and sustainability organizations like TNC to be sure that indigenous peoples and local communities are true partners in our work. As per the new report from the Rights and Resources Initiative (RRI), our starting point is to help secure rights for peoples who have been discriminated against for so long. And, to guide our future initiatives, we’ve recently released a new framework based on Voice, Choice and Action.

To mark International Day of the World’s Indigenous People, on August 9th, I would like to draw attention to our work in this area, and also extend the dialogue within TNC and our partners. Frankly, I’d love to hear views on the role that indigenous peoples should play in TNC’s activities going forwards.

What I am seeing is that, when we start with a people-centric, rights-based approach, engaging indigenous peoples and local communities as full partners, we have the opportunity to blend traditional knowledge and science with western knowledge and science. That may be one of our best shots at reorienting our relationship to the one home we have—Planet Earth.

They have much to teach us if we have the humility to listen.

Resources

-

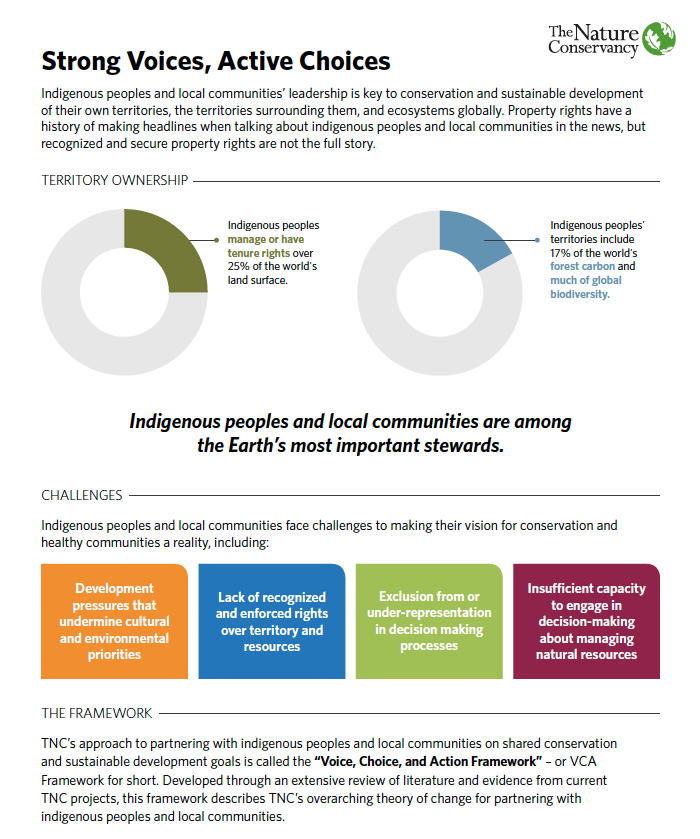

Infographic

PDF

Indigenous peoples and local communities' leadership is key to conservation and sustainable development of their own territories, the territories surrounding them, and ecosystems globally.

DOWNLOAD -

Strong Voices, Active Choices

PDF

Indigenous peoples and local communities are vital leaders in the pursuit of lasting solutions to the world’s most pressing conservation and development challenges.

DOWNLOAD