The Aquaculture Opportunity

Can the sector grow to provide seafood and jobs in harmony with the ocean?

Terry Sawyer comes from a long line of farmers and ranchers, and he’s learned a lot from his family—about maintaining the health of his broodstock and selecting the strongest performers for breeding; about managing the employees who help run his operation; and about the importance of stewardship and maintaining the health of the environment his farm depends on.

Sawyer’s work is unlike that of his parents and grandparents, though, in that he doesn’t worry about feed and water for his stock, and the sort of stewardship he’s concerned with has more to do with watersheds than landscapes. That’s because Sawyer, along with his partner John Finger, raises oysters, which require no food, land or freshwater.

Finger and Sawyer, co-owners of Hog Island Oyster Company, are part of the global aquaculture industry, which encompasses the farming of fin fish, shellfish and seaweed, in both marine and freshwater environments. When practiced well, aquaculture is one of most low-impact, resource-efficient ways of producing food. In fact, some forms of aquaculture, such as oyster cultivation, can actually help to restore coastal ecosystems.

This offers a reason for hope. We’ll likely see another 3 billion people on the planet by 2050, leading to a massive increase in demand for food, land and water. We have to find ways to feed the planet without increasing pressure on both terrestrial and marine habitats. Aquaculture, done well, offers a huge potential not just for producing food for a growing planet, but to provide livelihoods to coastal communities and, in the case of shellfish or seaweed culture, help recover lost ecosystem services.

If we get it right, aquaculture could be our best hope to sustainably feed the planet.

Assessing Environmental Impact

The idea of aquaculture as a sustainable food source might surprise some—in fact, many assume that aquaculture is an environmentally damaging practice. That reputation is not entirely unearned. Poor practices with salmon farming in in 1980s and 1990s and the ongoing destruction of mangroves to create shrimp ponds in some parts of South Asia, for example, have caused significant environmental damage and stained the reputation of the whole sector.

All forms of food production can have environmental impact, of course, including aquaculture. But new technology and lessons from the last forty years have led to better practices that are being adopted by substantial segments of the industry. Better siting practices, for example, ensure that fin fish can have less impact on the surrounding environment. While big challenges remain, the use of antibiotics for disease treatment and the amount of wild fish used in feeds has dramatically declined in some sectors.

Fish are far more efficient feeders than land-based livestock like beef, pork or even chicken; fish production also generates fewer carbon emissions and utilizes less fresh water and arable land per pound of production than their land based counterparts. With wild caught fish stocks in decline, fresh water sources overdrawn, and limited food production left in our soils, that greater efficiency is particularly important for food security.

Shellfish and seaweed are even more efficient feeders—they rarely require any additional inputs, feeding instead on ambient phytoplankton and nutrients. And in some cases, shellfish and seaweed don’t just require minimal inputs—they can actually improve the health of their immediate environment by removing impurities. Oysters can filter 50 gallons of water a day. Seaweed, too, is incredibly efficient at removing excess nutrients from the water, which can improve the health of eutrophic estuaries, like many in the United States, as well as carbon dioxide, which can mitigate ocean acidification in localized areas. Shellfish and seaweed farms also provide habitat for wild fish species and increase the diversity of species in sea beds, as can other forms of aquaculture infrastructure.

“There are all these problems facing coastal ecosystems—pollution, habitat loss, overfishing, the impacts of climate change—and depending on how and where aquaculture is done, you could make those challenges worse, or ameliorate them,” says Robert Jones, Global Aquaculture Lead at The Nature Conservancy. “That amelioration piece is really interesting. Our work to date has focused on figuring out when and where that’s possible.”

Infographic: Ecosystem Benefits of Aquaculture

Coastal ecosystems are threatened by coastal pollution, loss of habitat, overfishing and face an added threat amplifiers of climate change. When done in the right way and in the right places, commercial aquaculture can accelerate ecosystem recovery in addition to providing sustainable seafood and green jobs in coastal communities.

Collaborating With Industry

Bringing these efforts to scale, though, will require influencing a booming aquaculture industry.

“This is a really layered issue, with elements of sustainable and local food production, job creation, and environmental protection,” Jones says. “The opportunity we see is to shape the trajectory of the industry to not just minimize negative impacts, but also to become a food production sector with benefits for the environment, both indirect and direct.”

How that trajectory plays out could have a huge impact on the planet. Although the ocean covers 70 percent of the Earth, it currently produces just 2 percent of our food, including both marine aquaculture and wild caught fisheries. But when it comes to cultivating marine species for aquaculture, “we’ve just hit the tip of the iceberg,” Jones says.

Already the industry comprises over $150 billion in farm gate value—bigger than the global beef industry. Some estimates suggest that the industry could see another $200–400 billion in investments by 2050 in farm infrastructure alone. Combined with the growth in ancillary businesses, such feed innovations, grow-out technology, and animal health, aquaculture represents a massive potential for investment—and for environmental impact.

Infographic: Aquaculture Production and Growth

As new technologies and species develop, aquaculture will grow within new and existing geographies. Aquaculture is now the fastest growing form of food production on the planet, growing at an annual rate of 6% per year. Click on the image below for a larger version.

“There’s a huge influence opportunity right now,” says Maria Damanaki, former Global Managing Director for Oceans at The Nature Conservancy. “How can we direct innovation and growth in aquaculture towards opportunities that also improve aquaculture’s environmental performance?”

Fortunately, making aquaculture more sustainable doesn’t mean it has to be less profitable. In fact, most of the environmental challenges for aquaculture—habitat impact, over-reliance on wild forage fish for feed, disease, and genetic mingling of farmed and wild stocks—are also business challenges. For example, finfish aquaculture can’t continue to grow and be profitable without reducing its use of wild forage fish, which constitute 60 percent of operating costs for some operations. Siting fish pens in too-shallow water, a major source of negative environmental impact, is also bad for farmed fish stocks and cuts into operators’ bottom lines, as does disease in farmed stocks.

Quote: - Randall Brummet, The World Bank

Aquaculture, done in a socially and environmentally friendly manner, is the only way to meet the growing demand for seafood, while also creating jobs, generating revenues and taking pressure off over-stretched capture fisheries.”

“Industry needs help in these areas, and there is overlap between what we need to achieve as environmentalists and what they do as business people,” Jones says. “We’re not in the business of producing food, but we can help ensure food is produced with minimal environmental impact. We want to work with businesses and governments to create business opportunities and set up regulatory systems in ways that allow for growth, but are also protecting the environment.”

There are good reasons for aquaculture operators to welcome the involvement of environmental NGO’s like the Conservancy. NGOs can forge alliances and help to catalyze work on problems that are too expensive for any one organization to tackle. NGOs also bring a level of third-party credibility, Sawyer of Hog Island says—both with consumers concerned with environmental impacts and with farmers who need assistance navigating an often-slow moving regulatory environment. Those collaborations are vital for the long-term sustainability of the industry.

That’s especially important in deep-water open ocean farming, a segment of the industry that is beginning to shift from an experimental stage to a period of growth and maturity, says Brian O’Hanlon, founder of Open Blue, a company that grows cobia in deep water off the coast of Panama. “As early movers and pioneers in this space, we have a responsibility to create strong private, government, academic and NGO partnerships that will help ensure the industry develops responsibly at all levels.”

Infographic: Smart Growth in Aquaculture

Siting of aquaculture operations is the first and most critical consideration to minimize negative impacts of aquaculture operations. It is also a critical factor in determining the profitability of an aquaculture operation. To protect the environment and ensure economic growth, aquaculture operations should be sited in optimal locations based on environmental, economic, and social factors.

Local Communities, Global Impact

The Nature Conservancy is uniquely positioned to assist the industry with these goals, Damanaki says. “Aquaculture is essentially a hybrid of agriculture and fisheries, two sectors where we have a lot experience collaborating with industry. We’ve led some innovative work on finance for sustainable agriculture and siting and planning in the marine sector, as well as restorative shellfish work—we can apply all of that experience toward aquaculture.”

But the scope of the Conservancy’s work goes beyond mitigating negative impacts, she adds. “We know that aquaculture can provide sustainable food and jobs. We’re trying to show that it also can restore ecosystems.”

Project sites around the world are geared toward answering this question. Projects in California and the Chesapeake Bay, for example, are looking at the impact and potential benefit of oysters on water quality and eelgrass growth. In Indonesia and Belize, meanwhile, projects sites are focused on seaweed cultivation and its potential impacts on benthic ecosystems.

“Seaweed cultivation might seem like an insignificant aspect of global conservation, but in Indonesia, it really matters,” Jones says. Approximately 1 million people farm seaweed there, including some of country’s poorest citizens. In East Nusa Tengarra, where the Conservancy is working, there’s little arable farmland and fishing stocks have declined severely. “These people are facing the impacts of climate change day in and day out,” Jones says.

Seaweed cultivation offers a source of income with potentially little environmental impact—and that offers rare job opportunities in a region where empowering work for women has been scarce. The Conservancy works with residents locally, including indigenous groups, on the technical aspects of farming, including how to avoid damage to eelgrass beds and other natural habitats, as well as the economic and regulatory aspects of running an aquaculture business.

In Belize, a similar seaweed project focuses on assessing the potential habitat benefits of seaweed farms for commercially important coral reef dwelling species. Randy Tucker and Luis Godfrey, former fishermen who now grow seaweed with the Conservancy’s assistance, have already observed juvenile lobster, conch and hogfish returning to the areas where they’re cultivating seaweed.

“It gives me great pleasure to see these inhabitants hanging out in the seaweed we’re planting,” Godfrey says. If more fish return to the area, he and Tucker would like to bring tourists to their operation. “We’ll still go to out to Keys, but we’ll also bring them to the seaweed farm, too, and show them what we’re doing and tell them why.”

Godfrey says he’d like to see more young people join him in seaweed cultivation, especially those who might otherwise pursue fishing or lobstering. As in Indonesia, many of Belize’s wild stocks are overfished and declining, creating both environmental and economic problems. A growing aquaculture presence could address both issues—creating jobs and food while minimizing environmental impact.

“Meeting the growing demand for seafood is an enormous business opportunity for poverty alleviation,” says Randall Brummet, a senior fisheries specialist at the World Bank. “Aquaculture, done in a socially and environmentally friendly manner, is the only way to ramp up supply to meet this demand, creating jobs and generating revenues while taking pressure off over-stretched capture fisheries.”

And, for people like Luis Godfrey, aquaculture can offer not just a source of income, but a meaningful vocation.

“Just being in the water excites me, gives me more pleasure,” Godfrey says. “The sea life is my life.”

For those interested in learning more, or if you have questions or feedback, contact us at aquaculture@tnc.org.

Resources

-

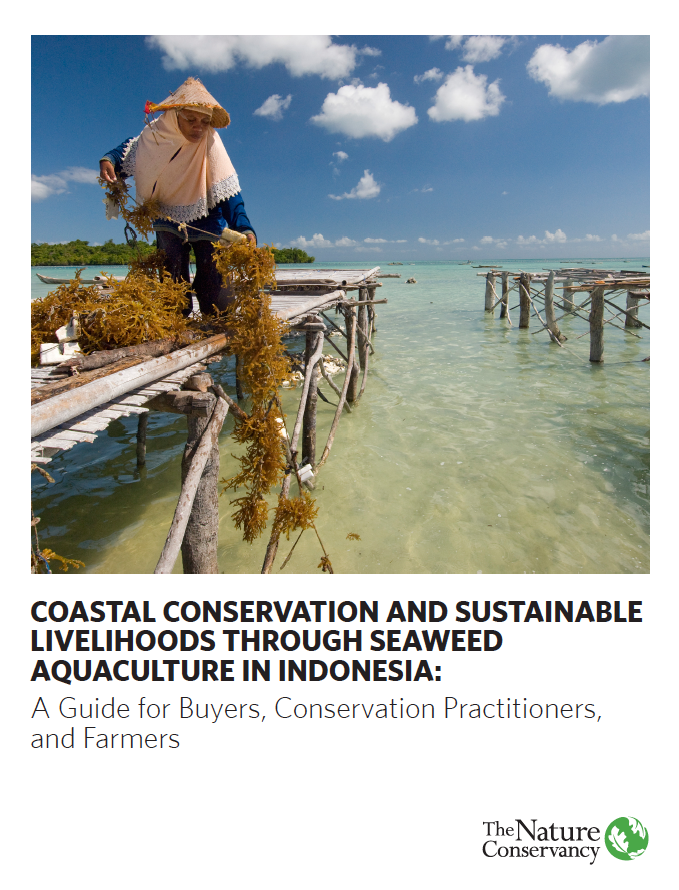

Indonesia Seaweed Guide

PDF

Coastal Conservation and Sustainable Livelihoods Through Seaweed Aquaculture in Indonesia: A guide for buyers, conservation practitioners, and farmers. Download in Indonesian

DOWNLOAD -

The Global Potential for Marine Aquaculture

PDF

A Science for Nature and People Partnership (SNAPP) report maps out the global potential for marine aquaculture.

DOWNLOAD

Global Insights

Check out our latest thinking and real-world solutions to some of the most complex challenges facing people and the planet today.