As coral reefs around the world are being lost at staggering rates to heatwaves, experts from The Nature Conservancy, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and Stanford University are racing to find and protect the most resilient of them.

The decline of coral reefs continues to make headlines. Corals are like the coal-mine canaries of the ocean, sensitive to changes in water temperature, chemistry and sediment levels. As the ocean warms, reef-bleaching heatwaves are becoming more frequent and more severe. Amazingly, some coral communities are surviving them.

Experts from The Nature Conservancy (TNC), Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and Stanford University are leading a collaborative effort to discover the secrets of these aptly named “super reefs” and help coral reefs persist in a warming world.

Coral Reefs Are Essential but Declining Rapidly

Coral reefs have evolved over hundreds of millions of years, and most of the established shallow-water reefs around today are older than the Pyramids of Giza. A healthy reef is an incredibly complex ecosystem.

“Ironically,” says Aldo Croquer, a marine program manager for TNC who coordinates reef restoration in the Dominican Republic, “that complexity comes from simplicity, because if you see a coral, it’s the most simple thing that you could ever imagine.” Tiny, sack-like and tentacled organisms, each farming glucose from microscopic plants within it, build underwater fortresses that teem with life.

The reefs that cover less than 1% of the world’s surface area support 25% of all marine life. They draw tourists to enrich the economies of coastal communities. They provide protection from the full force of waves that could otherwise damage homes and erode shorelines. Over 1 billion people around the world rely on them for food, livelihoods and, in some cases, the very land upon which they farm and live.

Yet reefs are in dramatic decline. “Globally, we have already lost 50% of coral reefs,” says Dr. Elizabeth McLeod, TNC’s global ocean director. “Some scientists predict that we could lose up to 90% by 2050 unless bold actions are taken to reduce climate change impacts and improve marine management.”

What is a Super Reef?

A super reef is a diverse coral community within a reef system that is more resistant or resilient to damaging heatwaves. Researchers are identifying where super reefs are located and which ones are best at spreading baby corals to other reefs. This information will help guide conservation and restoration efforts.

Why Are Some Coral Reefs More Resilient?

There are many factors that have contributed to the global loss of coral reefs, such as the use of dynamite to destroy reefs and release their fish for harvesting, pollution from sewage discharged into the ocean, and the smothering of reefs by sediment from development or deforestation. But ocean warming is one of the fastest-growing threats.

If temperatures rise above the comfort zone of corals for too long, the algae within the corals begin to produce toxins. The poisoned corals then eject the algae, losing both their color and their source of food in a single act. Corals can survive for some time on their internal energy stores or by ingesting organisms from their environment. But if these bleaching events occur too frequently, they cannot recover.

“These marine heatwaves are the weather equivalent of an atomic bomb,” says Dr. Anne Cohen, a tenured scientist who started the Super Reefs Program at WHOI in 2017. “The damage can be sudden and extensive, causing widespread bleaching and coral death in a single event. Nonetheless, we have observed diverse coral communities that survive these heatwaves with minimal impact and others that recover remarkably quickly.”

Are these reefs surviving heatwaves due to local ocean conditions? Are they genetically more heat tolerant? Or is it just luck? Addressing these questions and incorporating their answers into conservation efforts are critical to improving the prognosis of the world’s reefs.

“What we are doing is actually quite remarkable,” says Cohen. “We are uncovering nature’s secrets and using them to help her, as best we know how.”

Working Together in the Race to Save Reefs

Traditional reef conservation strategies are not enough in the face of climate change. An ecologically significant reef, shielded from overfishing and pollution in a carefully managed marine protected area, can still be devastated by ocean warming. A reef slated for demolition to make way for a new airport might actually be a heat-resistant super reef, whose billions of coral offspring could resettle degraded reefs if it were protected.

So a targeted, coordinated effort—like the joint super reefs partnership between TNC, WHOI and Stanford, with the participation of local conservation and government partners—is needed to locate and protect the world’s super reefs before they are lost.

“We don’t have a decade to get it right,” says McLeod. “And we need to be bringing our collective skills together. Time and funding are finite. This partnership allows us to prioritize our limited resources in the places that have the best chance of survival and support governments and communities leading the charge to save their reefs.”

First, the super reef partners engage community leaders, researchers, local groups and governments, building on TNC’s global network of coral reef projects to identify potential sites for reef conservation where there is local support and capacity.

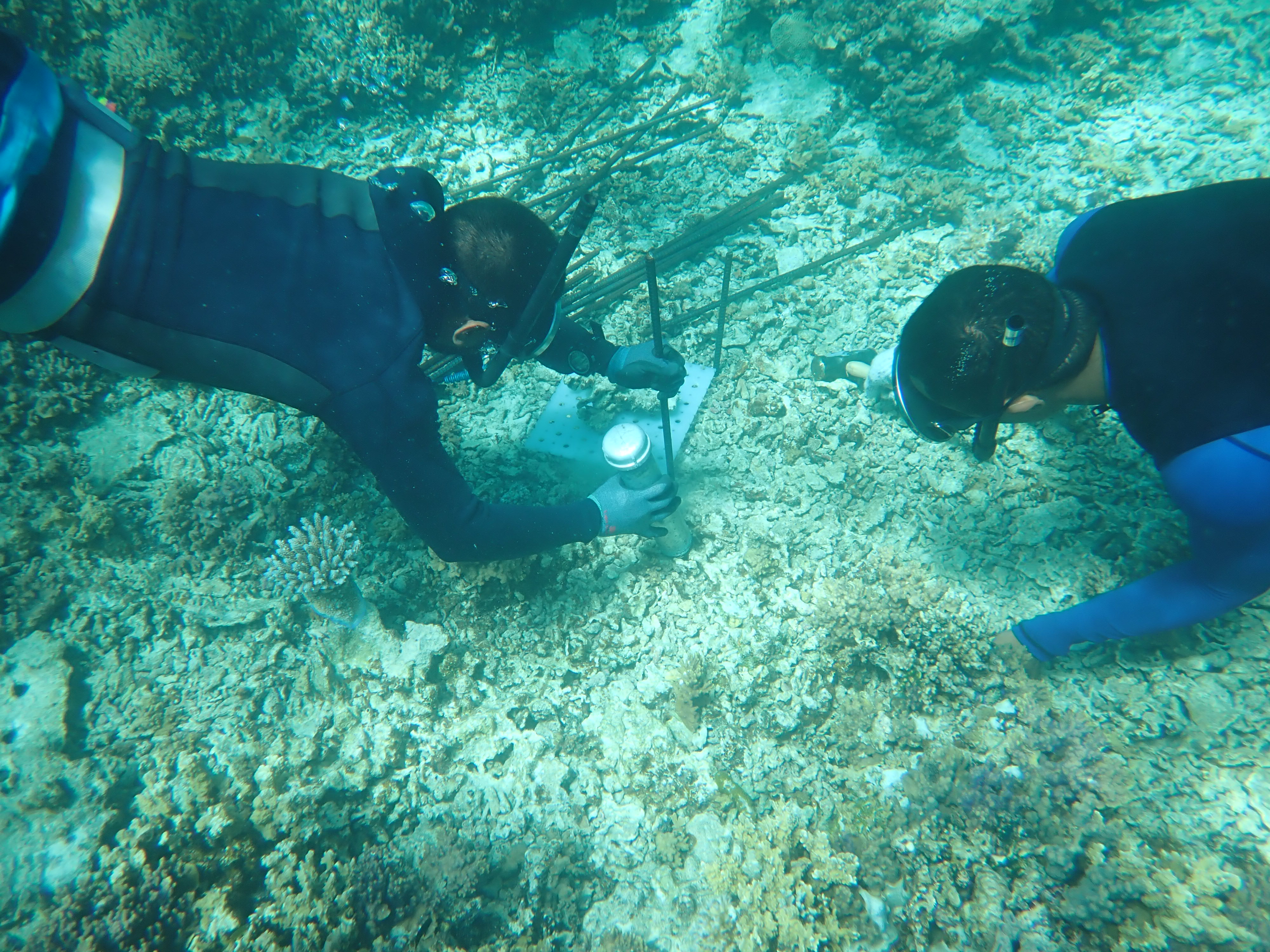

Divers place heat-resilient corals in restoration nursery sites made of metal rebar to study them.

Quote: Dr. Anne Cohen

We are uncovering nature’s secrets and using them to help her, as best we know how.

Then, Dr. Cohen and the WHOI team develop meter-scale, three-dimensional, hydrodynamic models of reef temperature and flow to predict where super reefs might be. Using survey data model output, the team evaluates how corals in target areas responded to, and recovered from, prior heatwaves. Areas that experienced intense heat with higher survival rates are good candidates for heat tolerance evaluation.

This is where the work of Dr. Stephen Palumbi, a marine geneticist from Stanford University, and teams of local students and conservation leaders comes in. They test multiple species of corals for heat resistance, quantifying the corals’ ability to withstand heat and future heatwaves and generating crucial data for super reefs research.

The WHOI team then runs larval dispersal simulations to quantify connectivity between super reefs sites and other reef areas. Areas that exhibit both high heat tolerance and an ability to reseed neighboring reefs are prioritized for the next step. TNC works with local partners to validate the model outputs with local data and support the protection and restoration of super reefs.

Quote: Dr. Stephen Palumbi

Our mission is to save as much as possible, so that when the world gets better—and it will get better, because this is going to be solved—then there’s something to grow back from.

Democratizing Science to Improve Research, Protection and Restoration

The key to reefs’ survival is not about a single, cure-all solution. “It is about the complex set of ecological conditions, human settings and situations that come together in the end,” says Palumbi. The science is one part of the story. The collaboration needed to expand its reach and put its conclusions into action is another.

A key feature of the super reefs project is the use of low-cost methods to identify heat-resistance in corals that can be replicated across multiple geographies, thus increasing the work’s pace and scale. Successful learnings can be rolled out through global knowledge-sharing networks, like the Reef Resilience Network initiated by TNC and NOAA’s Coral Reef Conservation Program, which connect marine practitioners around the world to the latest science and management approaches.

Ultimately, the best way to help reefs is to prevent their destruction in the first place. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions, improving the management of the world’s marine protected areas, and reef restoration are all important parts of the solution. The super reefs partnership improves reef conservation efforts by making them more effective under future, warmer conditions.

“Our mission is to save as much as possible, so that when the world gets better—and it will get better, because this is going to be solved—then there’s something to grow back from,” says Palumbi.

Global Insights

Check out our latest thinking and real-world solutions to some of the most complex challenges facing people and the planet today.