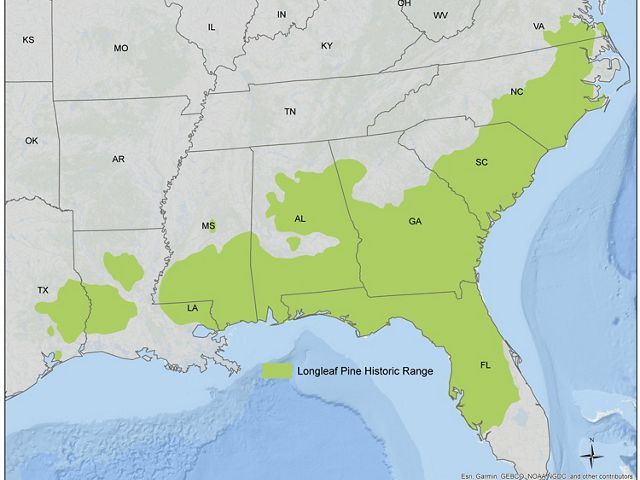

Five hundred years ago, a contiguous forest of longleaf pine trees covered 90 million acres, making it the dominant ecosystem of what is now the southeastern United States. Available in seemingly limitless supply, the trees were felled for their strong “heart pine” to build the homes, businesses and bridges of the growing country. Longleaf timber was also used in the construction of many early naval ships, including the USS Constitution, known as Old Ironsides.

By the 1990s, less than 3 million acres of longleaf pine remained. That 97% loss from an ecosystem is one of the most significant ever recorded, surpassing the decline of the Amazon rainforest and almost as great as the near disappearance of North America’s tallgrass prairies. Today, through extensive collaborative restoration efforts, longleaf pine acreage has risen to 4.7 million fragmented acres, approximately 5% of its original range.

One example of that recovery offered the U.S. Navy a chance to help the same kind of forest that provided timber to build ships centuries ago. “They were among the many partners that conserved a combined 27,000 acres of land on Georgia’s coast, where we have worked for decades to restore longleaf pine,” says Anne Flinn, The Nature Conservancy’s land protection director in Georgia. “This is a significant win for conservation, and limiting development helps the Navy achieve their mission at nearby Kings Bay Submarine Base.” The property includes some large blocks of longleaf forest, and partners will use tree plantings and prescribed fire to restore key areas.

Colette DeGarady, TNC’s longleaf pine whole system director, says TNC—which was drawn to the longleaf ecosystem for its biodiversity—is increasingly focused on how the species and the entire system can contribute to mitigating climate change.

“When we analyze climate resiliency data and overlay land conservation priorities, coastal properties such as this recent acquisition in Georgia rank high on the list for many reasons, including the buffer they can provide to sensitive, economically significant systems such as salt marsh that are particularly vulnerable to climate change,” says Colette.

SAVING THE SYSTEM

As longleaf pine forests have been cut and disconnected, the plants and animals they shelter have also struggled to endure.