Energy Sprawl

One TNC scientist has a vision for getting the energy we need without sacrificing nature.

Fall 2017

We all have places that we identify with, places that we’ll never forget, places that we can’t imagine will ever change. As a college student just starting my career as a scientist in the early 1990s, I spent time exploring the Pawnee National Grassland and enjoying the view of the buttes—two striking sandstone hills that rise from the vast, pan-flat grassland of eastern Colorado.

When I returned in 2007, a few years after I started working as the director of science for The Nature Conservancy in Wyoming, I was stunned by what I saw. The entire place had been transformed by wind turbines and natural gas drilling. When I parked at an overlook and gazed off toward the buttes, the view now included about 300 wind turbines dotting the Plains. And the surrounding parts of the National Grassland, which is managed by the USDA Forest Service, were marked by more than 60 oil and natural gas wells and all the roads that connected them.

I wondered, of all the vast, open expanses across the Great Plains, why is it that this place, my place, ended up on the chopping block? Is the wind that much better there? Is the natural gas that much more abundant? Even if it is, there has to be some way to pack the infrastructure closer together, to give it a smaller footprint on the landscape.

Today, as the lead scientist working for TNC’s Global Lands Program, I see the phenomenon of “energy sprawl”—widespread energy infrastructure development—as one of the most fundamental challenges that nature and humanity face in the coming decades. By 2030, an area at least the size of Minnesota could be converted to meet the projected energy needs in the U.S. alone. Around the world, we’ve estimated that 20 percent of the world’s remaining natural lands are under threat from energy development. To put that in perspective, that’s an area roughly the size of Russia.

Last year, the global community came together to recognize that we need to rein in emissions of climate-warming greenhouse gases. Since the energy sector represents the single largest contributor to climate change, many countries have agreed to phase out the dirtiest fossil fuels, such as coal, and they are increasingly turning to natural gas and renewable energy supplies, including wind, solar and biofuels. But the harsh reality is that these cleaner energy sources have a much a larger footprint on the landscape than coal. According to our estimates, it takes more than twice as much real estate to power a lightbulb from a solar development than from a coal mine. Wind energy takes seven times as much land. Biofuels? We would need to clear nearly 50 times the amount of land we would use for coal.

Climate change is a global challenge that society needs to address, but, in the process, we don’t want our solution to create another problem. By 2040, renewable energy sources like hydropower and biofuels are projected to double, while wind and solar will be 10 to 30 times our current capacity. If a country has set carbon goals for itself, clearing wild land for renewable energy development could create a carbon deficit that takes time to balance out. Globally, energy sprawl threatens hundreds of millions of acres of lands and hundreds of thousands of miles of rivers. Africa and South America, which still have the largest remaining areas of wild land, are also facing the greatest risk of being developed. Currently, only 5 percent of these lands are under strict protection in the form of parks or nature reserves.

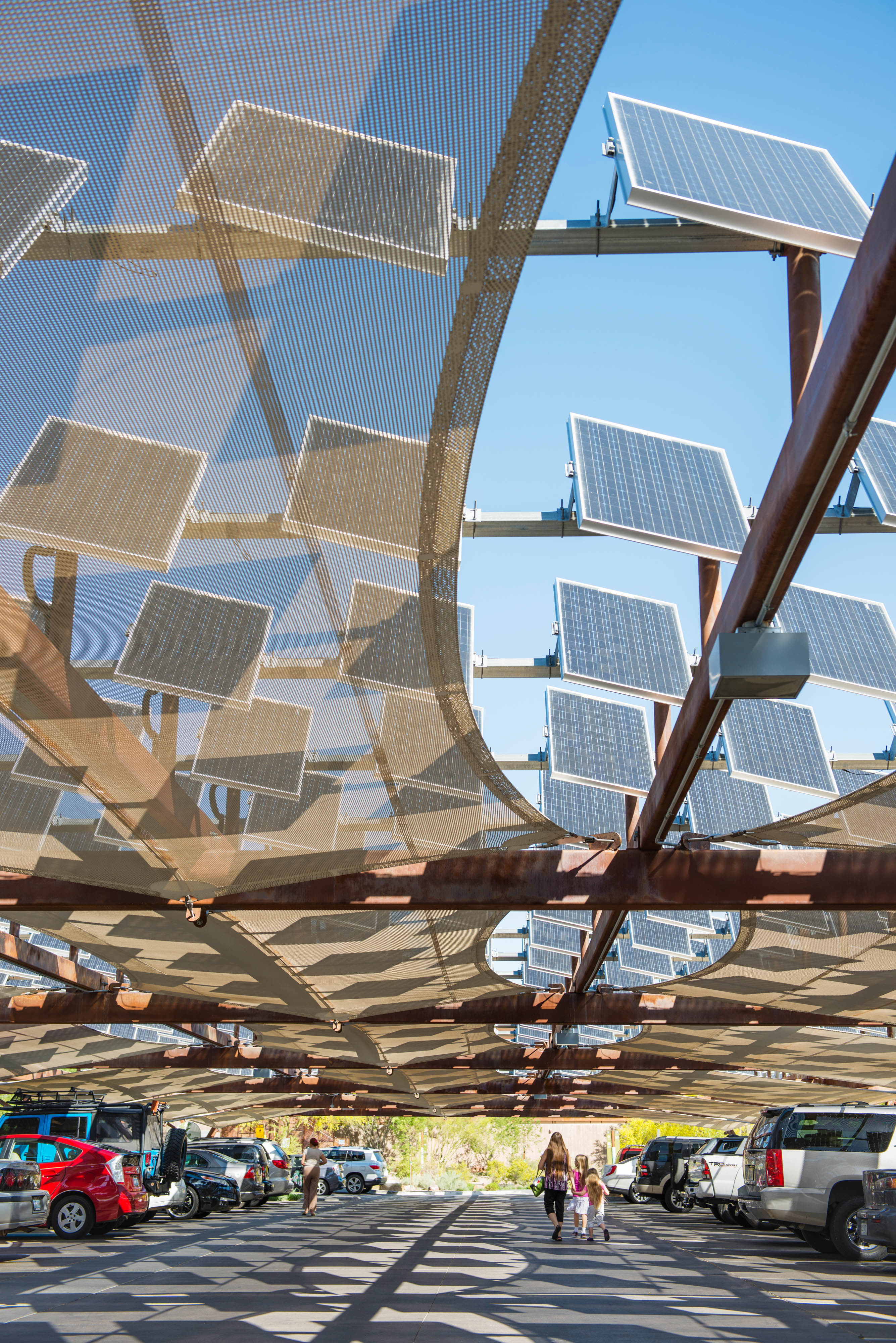

At TNC, we’re trying to face the challenge of energy sprawl by recognizing that a renewable energy future without a plan is not necessarily a green one. The idea is to get ahead of the problem by sketching out ways to reduce energy sprawl and to compensate for it in places where it’s inevitable. First, we try to encourage development to occur on agricultural lands, industrial areas, former mine sites and other converted lands. To avoid the need for new transmission wires, new wind and solar projects should make the most of existing transmission capacity from large retiring nuclear, coal or gas plants. Second, we work with governments and energy companies to come up with regional energy plans that avoid wild lands. Third, we promote siting energy production as close as possible to the places where it will be used, which sometimes means on the very rooftop of the house it will light up.

By helping to direct new development toward degraded lands or rooftops, we believe we can safeguard biodiversity, help the climate and smooth the development of renewable energy sources. In 2010, for example, our team in the Mojave Desert—a hot spot for solar development—mapped out the region’s most biologically diverse and unspoiled places. The maps have helped protect key habitat for species like the desert tortoise by steering industry development away from these locations. But our team also helped identify 1.4 million acres of previously developed or degraded sites that are well-suited for solar in the Mojave (old ranchlands, mines and the like). The Bureau of Land Management has already approved three proposed utility-scale solar energy projects in the Dry Lake Solar Energy Zone in Clark County, Nevada. The projects, which will generate a combined total of 480 megawatts of electricity on 3,083 acres, made it through the review phase in less than 10 months, less than half the length of time it has taken in the past.

We’re not just doing this with solar power. In Kansas and Oklahoma, for instance, TNC and its partners created a framework for power companies to select energy that comes from wind farms that are sited away from threatened ground-nesting birds, such as the greater and lesser prairie chicken. Our freshwater team has applied this strategy to rivers, such as the Penobscot in New England: We were able to tear down dams and reopen the main river to fish migrations without losing any electricity generation because the utility was able to retrofit dams far upriver to generate more power. In Europe’s western Balkans we are moving toward more comprehensive energy planning, working to figure out ways to use wind and solar on disturbed lands to eliminate the need for new hydropower altogether.

The key to making this approach work is by starting early to collaborate with governments and industry in order to come up with regional plans that keep as much biodiversity intact as possible. In 2008, for instance, Mongolia was experiencing an uptick in energy development in the form of mining for coal and uranium, as well as drilling for natural gas. Government officials came to us for help in balancing this development with the country’s commitment to set aside 30 percent of its lands for conservation. Mongolia has some of the world’s largest wild grasslands, the Eastern Steppe, along with Central Asia’s largest desert, the Gobi, where snow leopards prowl the mountains. (I spent two weeks looking for them, but didn’t spot any!) The government ended up using our analysis to protect more than 58,000 square miles across Mongolia—that’s an area the size of New York.

Many other developing countries are starting to invest in renewables in a major way, which offers a chance for them to develop a decentralized “smart grid.” India announced plans to quadruple its renewable energy capacity by 2022, which means installing 100 gigawatts of solar and 60 gigawatts of wind power. With more than 300 million of its citizens’ homes not even connected to the electric grid, India, like many developing countries, has a chance to leapfrog many developed countries by going straight to a dispersed model of renewable power generation. This would involve rooftop solar and smaller facilities, which will provide power to a greater number of people and concentrate energy corridors in areas that are already developed.

While it is bad news that wind, solar and biofuels all have a larger footprint on the land than fossil fuels, one of the great advantages of most renewable sources is that we can put them just about anywhere. Some places may be sunnier or windier than others, but renewables aren’t as tightly linked to a specific patch of ground as fossil fuels, and there are more than enough “good” places to site renewables that we can pick and choose. An analysis my colleagues and I have recently completed shows that there’s enough degraded land in the world that we can easily meet every country’s renewable energy goals by 2050 without clearing another acre of wild land.

In other words, if we choose, there need never be a conflict between conservation and renewable energy development. But we must start planning now.