American Icons

Four tree species that have helped shape American culture are under threat from invasive killers. Can scientists save them?

December 2014/January 2015

Along the upper reaches of the Connecticut River, Christian Marks is restoring what was destroyed. He and a team of volunteers are planting thousands of American elm trees where their ancestors, killed by disease, once stood. “There’s something romantic about it,” says Marks, a Massachusetts-based ecologist for The Nature Conservancy. “It’s a kind of nostalgia for an aesthetic that was lost from our landscape.” That landscape can be both physical and cultural.

When an icon like the elm is suddenly eliminated from a region, its significance can be measured by the size of the hole it leaves behind. Trees are woven into the fabric of American lives: They shade neighborhood streets and define cityscapes. They are the material of everyday objects—transformed into furniture, baseball bats, toys and homes. They feed the people and the animals around them, and they provide warmth and shelter. But even the greatest of cultural giants, the most well known trees, are vulnerable.

In the elm’s example, an invasive fungus killed millions of trees, radically altering city streets and forests in the eastern United States. Similarly, the American chestnut plummeted from ubiquity to near extinction across the Appalachians under the weight of disease, taking with it a vital source of food and timber.

As travel became easier for people and goods in the past 150 years, bugs and pathogens have been transplanted with disastrous effects. Invasive pests and diseases have killed billions of trees since the turn of the 20th century and cost more than $2 billion a year to remove nationwide. In response, researchers have bred trees immune to certain diseases, introduced new predators to attack insects and simply tried to slow down infestations long enough to find ways to stop them altogether.

They have their work cut out for them. There are many trees in trouble. Featured here only are some of the most recognizable, each representing different stages in the struggle against an invader.

Where ecologists once saw only losses, others like Marks now find hope. If an iconic tree like the American elm can nearly die off yet survive to make a comeback, there’s hope for other giants. It requires a bit of ingenuity and a lot of science, but the forests may just be more resilient for it.

1. White Ash

Species: Fraxinus americana

Range: Texas to Ontario, east to the Atlantic Ocean

Principal Threat: Emerald ash borer

Best Known For: The tree that hits home runs

The smell of peanuts, the feel of the summer sun, the cracking sound of the bat—baseball is classic summertime Americana. Less well known is the tree behind the game: the white ash. Batters have long favored the ash for its strength and springiness—so much so that nearly half the bats sold by Louisville Slugger are made of ash.

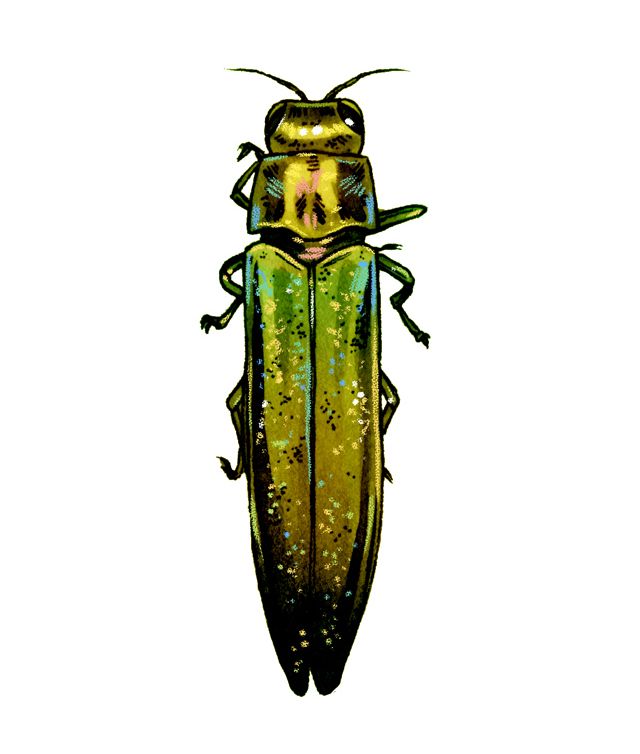

But this tradition may soon change. In the 1990s, an iridescent green beetle called the emerald ash borer hopped a ride into the country on a shipment from Asia, and it has had devastating effects ever since. By some estimates, the bug has already killed more than 50 million trees, and researchers are rushing to find new ways to stop it. The current treatment is costly, and the infestation must be fought one tree at a time.

To buy scientists time, the Conservancy, the Forest Service and even Louisville Slugger have tried to slow down the beetle’s dispersion by urging homeowners and campers to use local or heat-treated firewood. Transporting “firewood can spread [pests] and create new infestations,” says the Conservancy’s Leigh Greenwood, who manages the partnership’s campaign, Don’t Move Firewood. The campaign is meant to ultimately change wood-buying habits and give forest managers time to prepare for infestations.

Quote

By some estimates, the bug has already killed more than 50 million trees, and researchers are rushing to find new ways to stop it.

2. American Chestnut

Species: Castanea dentata

Range: Mississippi to Maine

Principal Threat: Chestnut blight

Best Known For: The toasty subject of "The Christmas Song" and American furniture

"Chestnuts roasting on an open fire …” the Christmas tune begins. Unfortunately, when Nat King Cole crooned those words in the 1940s, the American chestnut was in steep decline. For centuries, this economic powerhouse of a tree fed people, livestock and wildlife, and its timber was used for furniture, utility poles, railroads and much more. But at the turn of the 20th century, a foreign fungus began its sweep through Appalachian forests, where the American chestnut had once accounted for as many as one in four trees. By 1950, the species was almost entirely gone—leaving a less diverse and resilient forest in its place.

Restoring the chestnut requires breeding a new tree. For three decades, the American Chestnut Foundation has crossed surviving native trees with the Chinese chestnut, which is immune to the disease. They’ve developed hybrids, one of which is—genetically—more than 93 percent American chestnut but possesses the disease resistance of its Chinese cousin.

Nearly 10 years ago, 220 of these hybrid trees were planted at a Conservancy orchard in north-central Pennsylvania. Today, after the trees were deliberately infected to test their resistance, about 50 remain, says Scott Bearer, a Conservancy ecologist who manages the orchard. As resistant trees are identified at multiple test sites, American chestnuts are being bred and returned to the landscape after almost a century’s absence.

Quote

The American chestnut once accounted for as many as one in four trees in Appalachian forests. By 1950, the species was almost entirely gone.

3. Sugar Maple

Species: Acer saccharum

Range: Missouri to Nova Scotia

Principal Threat: Asian longhorned beetle

Best Known For: Red leaves in autumn and maple syrup in spring

Alex Wyss, director of conservation programs for the Conservancy in Tennessee, has seen his share of harmful bugs, but the Asian longhorned beetle, which looks like “something out of a sci-fi movie,” may be the scariest yet. “If we allow it [to spread],” he says, “it could be the end of the maple.” That includes the sugar maple, which is almost akin to the chestnut tree 100 years ago—culturally significant and economically crucial. New England’s annual $1 billion autumn foliage tourism sector relies on it, and in the United States, maple sap was boiled into more than 3.1 million gallons of syrup this year alone.

Some cities have quarantined themselves in the fight against the pest, and others have eradicated it by cutting down all infested trees. This year, the Conservancy brought its Don’t Move Firewood campaign to Great Smoky Mountains National Park in Tennessee. It’s the country’s most-visited national park, which makes it an easy port of entry for invasive insects. “We’ve been hit with a tsunami of pests over the past 10 years,” Wyss says. “We’re doing everything we can to prevent the [Asian longhorned beetle] from getting there.”

Quote

As of this writing, the Asian longhorned beetle had attacked 13 different types of trees, including willows and birches.

4. American Elm

Species: Ulmus americana

Range: Texas to Manitoba, east to the Atlantic Ocean

Principal Threat: Dutch elm disease

Best Known For: The tree that brought nature into America's emerging cityscapes

The reason “Elm Street” ranks as one of the most common road names in America can be traced back to 19th-century town planners, who favored the elm for its hardy nature. But by the 1930s, a foreign fungus known as Dutch elm disease struck and has since killed at least 43 million American elms in cities and forests, with some estimates citing even higher numbers.

Restoring them isn’t as simple as planting new trees, says Christian Marks, a Conservancy ecologist from New England. Very few surviving strains of the elm are able to resist the disease. But if only these similar trees were planted in their local ranges, the entire species would be vulnerable to new diseases. “That’s why we need genetic diversity,” says Marks.

Since 2010, Marks and his team have collected branches from surviving elms and bred new disease-resistant but genetically different trees. So far, they’ve planted 1,000 elms at 24 sites in the Connecticut River floodplain. They’ll plant thousands more in the coming years, and as the trees mature and produce seeds, the team expects the elm range to grow naturally to resemble what it once was. Even Elm Street might once again be graced with its namesake tree.