How Women Contribute to Conservation Around the World

Women help the global conservation community achieve success despite setbacks, obstacles, and a global pandemic.

The effort to protect our planet doesn't have time to ignore half its potential. Yet despite recent progress, women are still underrepresented in leadership and decision-making positions.

The first thing we must do is make the immense value women bring to conservation more visible. The next is to show what their work looks like. Here is a tiny fraction of the amazing conservation work women of TNC—and our partners—do every day.

Women have radical optimism in the face of unanticipated challenges

When the pandemic hit, Tara Poloskey discovered her job was suddenly very different. As an education and outreach coordinator for TNC in Texas, she usually gives tours of TNC preserves and helps people better understand—and love—nature.

When in-person events were no longer safe due to the virus, preserve tours were no longer possible. Meanwhile, TNC’s ponderosa pine restoration project, which depended on critical genetic work in 2020, was at a standstill. Poloskey saw an opportunity.

“I couldn’t wait to get out there,” she said, still coming down from the high of being alone in nature for days at a time. And she was truly alone: from July through October 2020, she spent four-day stints in west Texas’s mountains (going home in between to spend time with her dogs).

“There were plenty of elk and deer. Birds that bird watchers would fall over themselves to see, I saw those every day,” she says casually. “Rattlesnakes, too. I saw a jet-black diamondback, which I’d never seen before.” The only human she encountered was one volunteer who assisted her at the highest altitudes.

Poloskey’s job was to collect pine needles from mountainside ponderosa pine trees—during monsoon season. Her days started before dawn to give her enough time to drive 45 minutes to the collection site, hike deeper in the forest while lugging a 17-foot pole saw, collect pine needles from tree branches more than 20-feet over head, and get down before the monsoons started in the afternoon. It was physically demanding.

“In the pandemic I hadn’t exercised like I should have,” she said, “but after I felt like my lungs were twice the size they were before. It felt so good.”

Poloskey says that people are surprised to hear what she did because she’s a woman. But she grew up outdoors and, as a biologist, did field work in extreme environments. “I love being out in nature testing my survival skills,” she said. “A lot of people don’t push themselves beyond their fears. You’re more capable than you think, and you’ll surprise yourself by what you can accomplish.”

Sue Wicks gets that a lot, too. But she’s no stranger to pushing herself, a quality she relied on as an inaugural player in the WNBA and, now, as an oyster farmer during a global pandemic. She talks about how difficult it was to get her oyster farm up and running, the difficulty in transitioning to direct to consumer selling after the COVID-19 pandemic eliminated most of her restaurant sales, and of the daunting and ever-present challenge of climate change.

Quote: Sue Wicks

What's better than creating a whole new green economy? It's a layup, an easy win.

“In sports, we analyze numbers all the time,” she says, admitting that she may not have gone into oyster farming had she known what was coming. “You don’t know the difficulties you’ll encounter.”

Wicks’ livelihood depends on both a healthy environment and a healthy economy. Her wildly varied background as a basketball star and economist gives her a uniquely valuable perspective and drive that’s welcomed in the oyster farming and conservation communities. She describes having a radical optimism that helps her meet new challenges again and again.

This optimism-fueled drive had benefits. The exposure that oysters received due to the pandemic meant regular people learned about the oyster farmer predicament. “We became another face of the impact to local businesses,” says Wicks. “We got new people interested in oysters, but also in aquaculture and the environment.”

As a former WNBA all-star, Wicks knows what a sure shot is. But as an economist, she asks, “What’s better than creating a whole new green economy? It’s a layup, an easy win.” Women are necessary to growing these sustainable economies. “They bring a different spin to everything,” she says.

Women innovate and build conservation partnerships

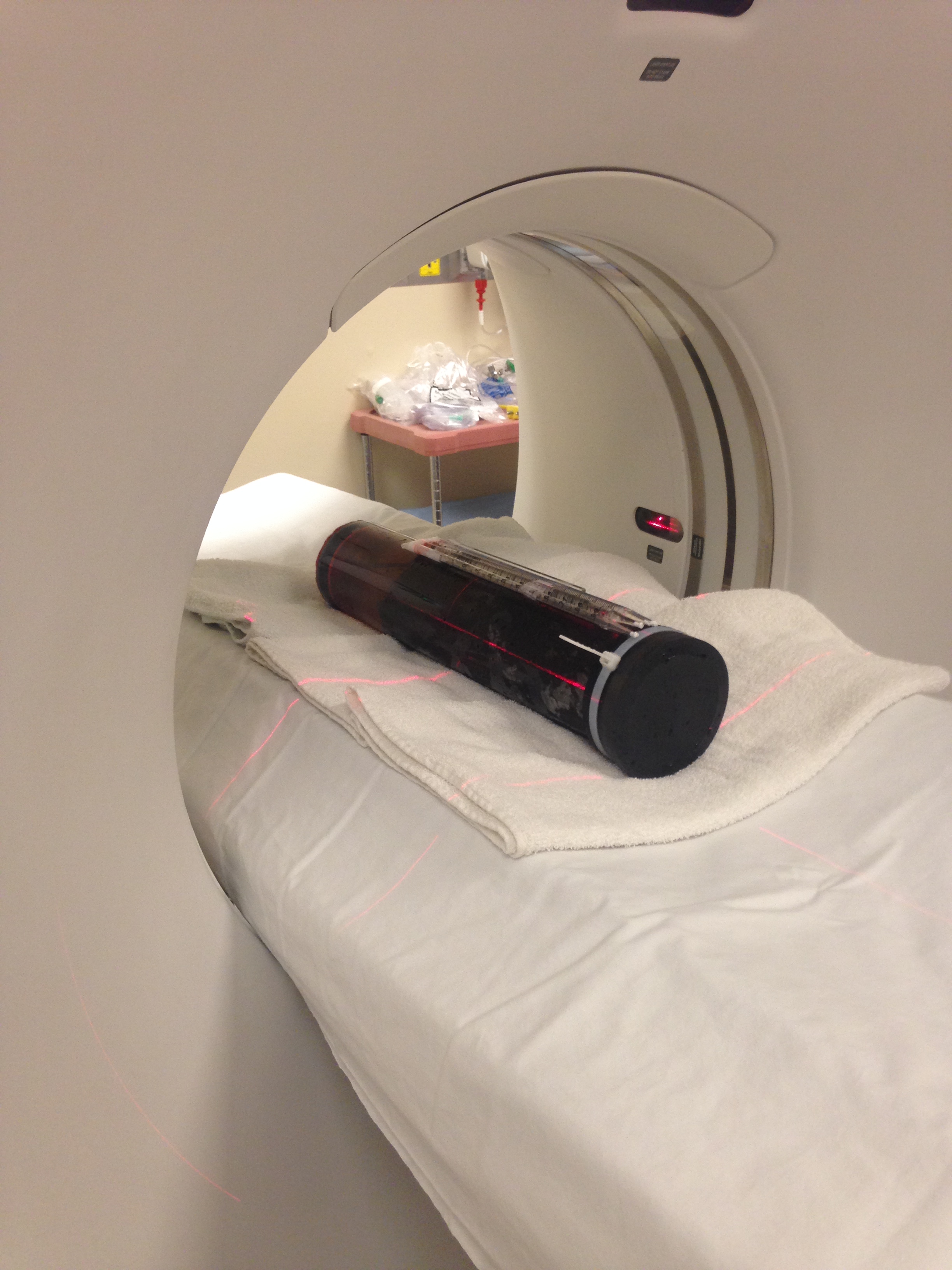

That whole new green economy is being increasingly recognized as a necessity with each new natural disaster. After Hurricane Sandy hit New York in 2012, over a billion dollars was made available for upgrading sewage treatment plants. One unexpected beneficiary? Salt marshes in the area where wastewater flows. It was time to check on the health of the marsh—and a CT scan was in order.

Quote: Nicole Maher

Nature and people need clean water to thrive. How quickly can nature heal when we give it the clean water it needs?

Nicole Maher, senior coastal scientist for TNC in New York, excitedly wheeled muddy salt marsh cores through the back door of Northwell Health Imaging Center in September 2019. This happy partnership (the imaging center enthusiastically donated their time and resources) brought medical technology to conservation science. Maher usually spends her days either in an office or along the coastline and welcomed the change of scenery.

The center’s technologist welcomed seeing a different type of patient. She placed the salt marsh cores in the cat scan machine, programed to examine a person’s lungs. This works because salt marsh roots are structurally very similar to human lung tissues: they’re filled with air to oxygenate the soil around them.

Salt marshes evolved to live in low nutrient environments, putting lots of roots and rhizomes belowground to find nutrients. When there’s an abundance of nutrients, such as nitrogen from sewage treatment plants, marshes don’t need to invest as much in that belowground growth. The result can be reduced root growth and flimsier grass shoots.

This is disastrous during major storm events. Healthy salt marshes—with a solid network of roots belowground and stiff grass blades— absorb wave energy from storms, protecting coastal communities and infrastructure in the process. Sick marshes offer much less protection. Above ground, salt marshes can look perfectly healthy, but it’s what’s beneath the surface that counts.

New York had the ideal salt marsh environments for testing sewage treatment plant upgrades. When the project is finished, wastewater will bypass the coastal bay, eliminating much of the pollution that’s been harming the salt marshes. In a few years, Maher will bring new cores to the imaging center to measure how fast the marshes respond to the improved water quality.

“We know that both nature and people need clean water to thrive and be resilient in the face of climate change,” says Maher. “This is an exciting opportunity to measure nature’s response to dramatic water quality improvements. How quickly can nature heal when we give it the clean water it needs?” Time will tell.

Quote: Catherine Schloegel

We need help. This isn't something two or three people at TNC can do.

In Colorado, Catherine Schloegel is racing to answer a question: how do you get a seed to become a tree? On the surface it seems simple enough.

However, as the watershed forest manager for TNC in Colorado, she knows the answer is not so straightforward. The tried-and-true method of growing trees in nurseries and planting them by hand is expensive and limited by infrastructure and to areas that are easily accessible. Schloegel wants to learn how we can make reforestation cheaper and easier to accomplish in places far from roads.

It’s a race to find out what will work, she says, because wildfires in Colorado have been more frequent and more severe since the 1970s. In fact, 2020 brought the worst wildfires Colorado has ever seen.

Normally, a forest can recover from wildfire on its own. “Fires are now burning over past fires, called reburns,” says Schloegel. These reburns leave large burn scars with no surviving cone-bearing trees. Without the cones—and the seeds they contain—these burn scars are unable to regenerate as forests. If we don’t step in, forests can transition to grasslands, resulting in a loss of carbon storage and the water, wildlife and recreation benefits that forests provide.

Collaborating with her team and partners, she tested several simple machines and processes, some successful but with several failures along the way. One test used a seed bike: a modified bicycle that turns a barrel filled with seeds, clay, manure, water, and chili powder (to deter foragers).

"It didn't work," says Schloegel. “We quickly test, plant, and eliminate methods that don’t work. Any approach we use must be adapted to local ecology, and Colorado is very dry compared to other regions.”

Normally, she’ll work with regional scientists, partner with the private sector, and engage with the public. “We need help,” she says. “This isn’t something two or three people at TNC can do.” Due to COVID-19, there’s a limited potential for working together to solve this problem.

“We need science but we need people,” says Schloegel. “We need to work collaboratively to build the knowledge and momentum to restore Colorado’s forests.”

Women support Indigenous conservation

Like women, Indigenous peoples have historically been left out of conservation decision-making. Yet Indigenous peoples, and especially Indigenous women, are more directly dependent on natural resources and inhabit areas that are more vulnerable to climate change. Some women within TNC are working to change this reality and increase Indigenous women’s participation in conservation programs.

In the Solomon Islands, more than 80% of people live in rural areas and are heavily dependent on marine and forest resources for their basic livelihoods. As populations grow, these natural resources are being exhausted.

“My parents and elders in the communities will tell me how we used to have bigger fish in these rivers, but now we can barely see them,” says Madlyn Lagusu Ero. “There’s a great possibility that our children may only hear stories of these resources and not actually see them.”

Ero is a conservation practitioner in the Solomon Islands focusing on gender work in conservation. She explains that men and women interact with their environments differently. For example, knowledge of certain herbs is passed down only through generations of women.

"What's important to women may not be equally important to men due to this different usage of resources," says Ero. Without women helping to make conservation decisions, these resources may not have as much protection.

Conservation programs like hers help local communities ensure vital resources are sustainably managed so that they can continue to support future generations. Historically, logging forests has been the Solomon Islands’ most significant foreign export, but recently mining has become the new economical drive. Since mining is so new here, communities have little experience with the industry and little information is available on its impacts or benefits.

Ero leads a mining awareness program to help landowners make informed choices. Her team has trained more than 40 community facilitators who have reached out to 16,000 people with flip charts and films on mining and its benefits and impacts. These awareness materials specifically target women in the communities.

Turtle Advocates

Women in the Solomon Islands protect turtles with conservation education and ecotourism.

Meet the KAWAKI Women’s Group“There is a real concern that the communities that are more affected by mining may not receive the promised benefits,” says Ero. “Over the years, I’ve seen women grow confident and raise their voices on mining issues in their communities.”

On the opposite hemisphere, Luciana Lima and Rafaela Carvalho help to ensure Indigenous peoples, especially women, have a voice in conservation in Brazil.

Carvalho, an Indigenous conservation assistant for TNC in Brazil, is part of a group within the government of the State of Pará that supports women leaders in addressing public climate policies that benefit Indigenous peoples. Before, there was no representation of Indigenous women in conservation decision-making, but now women are in prominent roles.

In the Oiapoque region of Brazil, Indigenous women are responsible for natural resource management, preserving traditional knowledge of medicinal plants, and addressing problems related to climate change. Women in this area have created a “green pharmacy,” where they exchange medicinal plants. Carvalho regularly meets with the women and helps monitor their conservation activities. She believes that her empathy and patience strengthen her communication with Indigenous women.

“When we talk about conservation, we must include Indigenous lands because they help preserve biodiversity,” says Carvalho. “Indigenous women are prominent figures in these conservation activities.”

Lima, a field manager for TNC in the Xingu region of Brazil, promotes conservation and the sustainable use of natural resources in Indigenous lands and territories. She meets weekly with Indigenous women and partners to discuss strategies to implement the Indigenous land management plans.

Certain activities, such as producing babassu oil and babassu flour and making handicrafts, are developed exclusively by women. Lima sees an opportunity to make these natural products available within government-run institutions, including public schools, and hopes to access public policies aimed at production.

Quote: Luciana Lima

Thanks to women’s leadership, Indigenous communities in Brazil are preserving nature, mitigating climate change, and strengthening their cultures for present and future generations.

“Indigenous women are the great ancestral wisdom holders of their territories,” says Lima. “They are the ones who plant, harvest, and produce new products. They believe in a legally-generated income from healthy products that strengthen their autonomy and community recognition.”

By advancing their own autonomy, these women advance the autonomy of all members of their communities, encouraging sustainable management and protection of their territories.

Today, some of the results from these partnerships include increased participation of women in conservation decision-making, more women on organizational boards representing the needs of their people, and women involved in conservation actions. They have also seen economic growth—in fact, some women are the only income earners in their family.

“Thanks to women’s leadership,” says Lima, “Indigenous communities in Brazil are preserving nature, mitigating climate change, and strengthening their cultures and the well-being of present and future generations.”

A woman’s work never ends

Despite the much-needed contributions women make to conservation every day, their work doesn’t always end at 5pm. Unpaid domestic responsibilities still largely fall on women’s shoulders, even in wealthier countries and even when women have jobs outside the home (a trend that the COVID-19 pandemic has only exacerbated).

Like many women in the Solomon Islands and around the world, Ero returns home at the end of the workday to prepare dinner for her family. On Saturdays, she takes care of the laundry, house cleaning, and shopping for food for the upcoming week.

Quote: Tara Poloskey

Regardless of what you think you can do, if it calls you, you need to answer. Don’t let someone else answer for you.

The weekend is also when Ero is involved in various non-work community obligations. Like many women in conservation, she feels a responsibility to grow a love of nature in her community. However, this often happens outside of working hours.

She noticed that youth, who now have increased access to formal education, have been disconnected from traditional knowledge of the forest’s natural resources and cultural significance. So, one year, Ero organized women and men in her community to spend their Christmas week teaching community youths the traditional knowledge of their forests.

In New York, coastal scientist Maher spoke with a troop of young Girl Scouts—one of the members was the daughter of the CT technologist who performed the scans. Although the girls were just eight years old, they eagerly discussed water quality issues and looked at water quality treatment plants as an alternative septic system. They learned that if they like to go to the beach and play in the water, they need to help care for their environment. Perhaps one of these girls will grow up to help manage these same habitats.

Poloskey suspects that if she were one of the stereotypically rugged, male preserve managers she often works with, her solo pine needle gathering expedition probably wouldn’t have been news. But that doesn’t bother her. “I want young women and girls to feel they can do this, too,” she says. Poloskey is inspired to speak to young women who may not feel they have this level of freedom to choose a career outdoors.

“Regardless of what you think you can do or what you think is acceptable, if it calls you, you need to answer,” she advises. “Don’t let someone else answer for you. It might help save something that’s as enormous as a ponderosa pine.”

And for basketball-player-turned-oyster-farmer Sue Wicks, whose very livelihood depends on a thriving environment and economy, her radical optimism surfaces once again. In the middle of the pandemic, she watched families walk up and down the beach, enjoying nature. “I’ve never seen people do that so much,” she says. “People reconnected with the beauty around them that they didn’t even know they had access to before.”

She's already looking ahead to when people will be able to celebrate with oysters in restaurants again. “There will be lots of oysters and champagne in our future,” she hopes.

We Need People of All Genders to Work in Conservation

It's not just scientists that contribute to our conservation success—we have many different job types! See how you might fit in at The Nature Conservancy.