The Volgenau Virginia Coast Reserve Story

Reflections on protecting a coastal wilderness and looking ahead to our next half century of conservation.

Island in the Crosshairs

In January of 1955, an Eastern Shore newspaper reported that the United States Navy had a plan for Parramore Island, the largest of Virginia’s barrier islands. The Navy would use condemnation to take ownership of Parramore and turn the island into a bombing range.

Other than Assateague, Parramore was the only island in the system featuring an old-growth maritime forest. This rare resource would fall squarely in the crosshairs of the Navy’s two proposed 6,000-foot-diameter target areas, virtually assuring its destruction. Migratory birds and other wildlife dependent on this habitat would face immeasurable peril.

Through an intermediary, Parramore’s owners reached out to George Fell, The Nature Conservancy’s executive director at the time, suggesting that the island be protected as a wildlife refuge.

The idea would take nearly 20 years to come to full fruition, yet it set in motion a dynamic that continues to this day: local people joining in partnership with TNC to defend their home and to protect the lands and waters on which their lives depend.

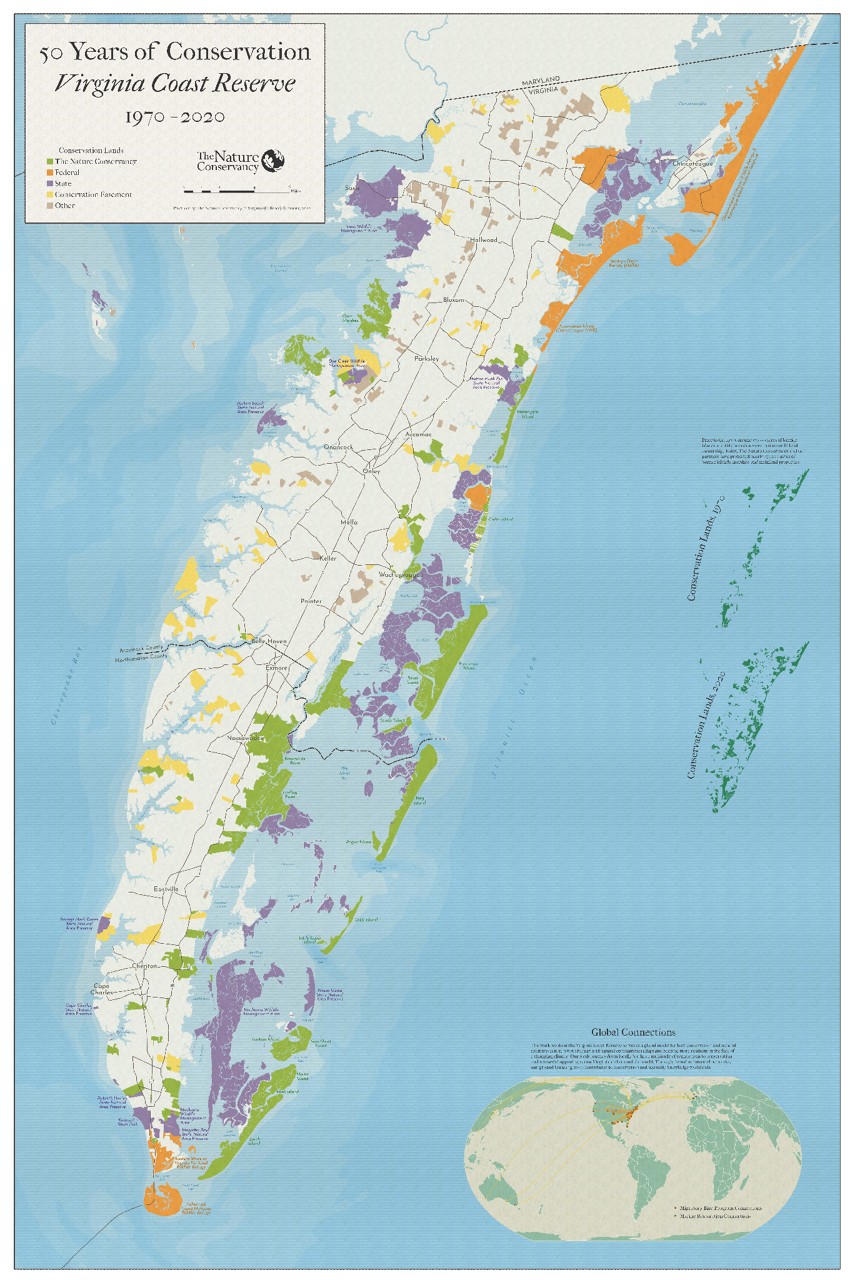

50 Years of History

If a picture is worth 1,000 words, our new interactive story map must be priceless.

Explore the Story MapAn Alarming Development

In those days, The Nature Conservancy was a fledgling organization with minimal influence and resources. TNC’s quest to protect the islands began, necessarily, as grassroots letter-writing and outreach campaigns.

The small conservation community, local Chamber of Commerce and watermen found themselves in an exceedingly rare alignment for the time over threats to wild habitat and to commercial and recreational fishing grounds.

The Navy eventually dropped its plans in the face of such unexpected, united opposition, but as the 1960s wound down, a massive new development threat suddenly loomed. In late 1969, the New York-based Smith Island Development Corporation announced that it had purchased Smith, Myrtle and Ship Shoal islands and planned to build a $150 million resort and second-home community for at least 40,000 people.

The Power of Partnership

A New York Times article highlighted the development scheme in February 1970, helping revive and bring new urgency to negotiations involving TNC and island landowners. Patrick Noonan (who would rise to TNC president a few years later) was leading the organization’s renewed efforts when a series of fortunate events resulted in an epiphany.

Noonan was visiting the islands and discussing conservation options with trustee Ed Bentley and representatives from The Mary Flagler Cary Charitable Trust when the proverbial lightbulb clicked on. According to the Cary Trust’s Ned Ames, that’s when the realization surfaced that, working together, they had an opportunity to protect not only a tract here and there, but an entire barrier island ecosystem.

By year’s end, TNC would acquire Godwin and Hog islands and would purchase Smith, Myrtle and Ship Shoal islands from Smith Island Development Corp. Having now consolidated five islands under conservation management—and cemented a powerful partnership with the like-minded Cary Trust—TNC had protected the core of the Virginia Coast Reserve.

Years of persistence and relationship building finally bore fruit in 1973, when TNC added Parramore, a crown jewel in the island chain. By 1975, the Cary Trust had invested nearly $8 million in The Nature Conservancy’s conservation work on the Eastern Shore.

As a result of these combined efforts, the Virginia Coast Reserve encompassed nearly all of 14 islands—then, as now, the longest stretch of wilderness along the nation’s entire Atlantic coastline.

A Living Laboratory for the World

An early sticking point in negotiations to acquire Parramore Island had been plans for its ongoing stewardship. The owners preferred it to remain privately owned, whereas TNC, until then, had generally looked to hand off land acquisitions to an appropriate local, state or federal agency. (Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge is an iconic example from this era.)

In hindsight, this disagreement and delay proved to be for the best. By the time TNC assembled the Virginia Coast Reserve, it had grown and evolved into an organization prepared to make a long-term commitment to the Eastern Shore of Virginia.

As visionary as our TNC colleagues and partners were in 1970, no one back then could have fully predicted that, by putting down deep roots in the local community, we would also be an inspiration around the globe. But that’s precisely what has come to pass.

As it embarks on its next half-century, the Volgenau Virginia Coast Reserve stands out as one of the most important living laboratories in the world. Having piloted community-based conservation, contributed landmark migratory bird research and pioneered techniques for restoring critical habitats such as oyster reefs and seagrass meadows, the Volgenau Virginia Coast Reserve continues to produce groundbreaking science and innovative conservation.

Today, the barrier and marsh islands of the Volgenau Virginia Coast Reserve—along with thousands of additional coastal acres TNC subsequently protected—hold the key to restoring natural coastal systems and to protecting coastal communities around the world from the harshest impacts of climate change.

TNC conservation scientists and partners are unlocking more new knowledge by the day, offering reasons for optimism as we face the environmental challenges of our time.

Download

We Can’t Save Nature Without You

Sign up to receive monthly conservation news and updates from Virginia. Get a preview of Virginia's Nature News email