Recovering the Past: A History That Mirrors My Own

VVCR History Intern Vanessa Moses reflects on the enslaved individuals who built what is now Brownsville Preserve, and finds connections across time in her own family's history.

Vanessa Moses is an Eastern Shore of Virginia native. She double majored in African American Studies and Environmental Thought & Practice at the University of Virginia, obtaining her bachelors degree in 2019. She taught English in the Baltimore City Public School System before returning to the Shore to work for The Nature Conservancy. As the Brownsville History Intern she engaged in environmental, historical and genealogical research. She hopes her work inspires others to trace their lineage and take pride in the environment where they reside.

I didn’t return to the Eastern Shore of Virginia with the intention of beginning a career in historical research.

I moved back to the Shore for support and familiarity after a challenging spell as an English teacher in Baltimore City during the COVID-19 pandemic. As a Shore native, there are certain unspoken pleasures of being back in a rural community—a slower pace, smiles from cashiers that ask, “How ya mama doing?”, familiar and familial faces.

From the perspective of a nature lover, the Eastern Shore also pulled me back for some of the best stargazing East of the Mississippi, the sights and sounds of the Chesapeake Bay and the availability of forest to forage for pawpaws and blackberries. A summer home seemed more positive than fleeting, even though I had some reservations about leaving the excitement of the city.

Uncovering History and Building Relationships

The Brownsville History Intern position lured me home because it was unique. The Nature Conservancy has historically focused on the preservation of landscapes and endangered species, but as the organization has grown, there has been a stronger emphasis on the interdisciplinary nature of conservation efforts.

To save species, spaces and ecosystems, organizations need to develop relationships with the local community beyond visiting cafes in town and sponsoring events. The Brownsville History project in Nassawadox, Virginia was an endeavor to strengthen community ties by engaging one of the most underserved groups, the local African American community. The project sought to understand more about the enslaved individuals that occupied and worked the landscape of Brownsville, a former plantation acquired by TNC in the 1970s as a part of the Volgenau Virginia Coast Reserve.

Quote

The enslaved individuals at Brownsville were the structure of the plantation. Their contributions were great, but their individuality and perspectives were rarely documented in the historical record.

For decades, employees of TNC's Brownsville Preserve were aware of the former owners of the plantation. There were collections of portraits, books and trinkets owned by the white Upshur family still housed in Brownsville manor.

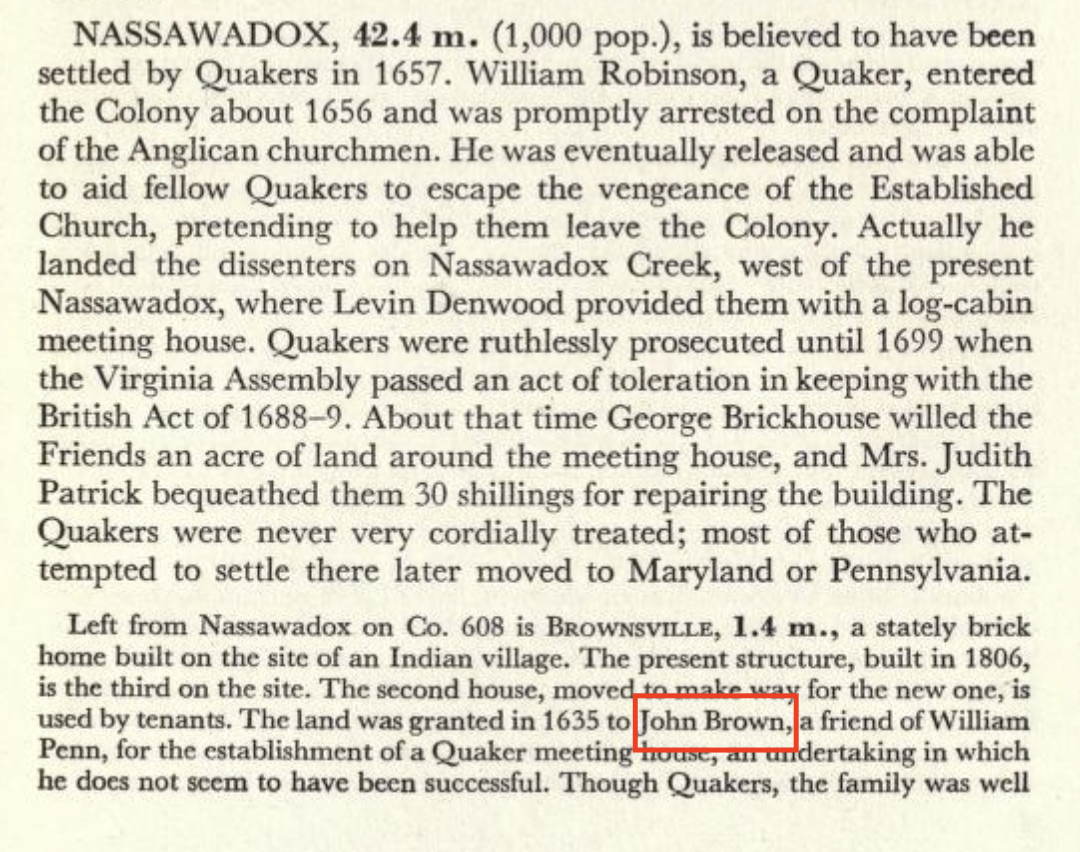

These Upshurs were descendants of a Quaker named John Brown (no relation to the Abolitionist leader), an acquaintance of William Penn, well known for establishing the American Colony of Pennsylvania. In 1635, Brown was granted land on the Eastern Shore to establish a Quaker meeting house in Northampton County, Virginia. When Brown’s efforts to create a Quaker community failed, he stayed in the area and married into the already established Upshur family.

For generations, the white Upshur family built wealth through slaveholding and the production of cash crops such as tobacco, corn, barley, castor oil and even rosewater. These descendants of Brownsville became doctors , attorneys, state legislators—so many achievements that an Upshur Family book was published to record their lineage and accomplishments.

But what did anyone know of the Black Upshurs? These enslaved individuals were given the Upshur surname to denote the people that owned them and the area they occupied, not their heritage. However, the enslaved individuals at Brownsville were the structure of the plantation. Their contributions were great, but their individuality and perspectives were rarely documented in the historical record.

When I accepted the position as the Brownsville History Intern, I accepted a challenge. This exploration of the Black Upshurs wouldn’t be smooth, but I anticipated that I would find more of my own history as a Black Eastern Shore native in the process.

Quote

Engaging in genealogical research was an exercise in patience. Sometimes, I would learn that a person knew how to read, or left the Shore for a job opportunity up North, and then suddenly they’d just be… gone.

Asking Questions and Building Understanding

The Eastern Shore is small, so the first step in understanding the lives of the Black descendants of Brownsville was word of mouth—I asked my mother questions about growing up in Northampton County, I tabled at the local Juneteenth celebration and I asked TNC employees what they knew about Brownsville. There were leads:

“I think the Upshurs had a store in Nassawadox."

“I know some Upshur’s went to the AME church in Franktown.”

These tidbits were a launch point, so I proceeded to investigate local cemeteries and ask local businesses what they knew about former storekeepers.

The next step was to track down historical documents that illuminated more about the lives of the Black descendants of Brownsville. My supervisor, Jennifer Miller (VVCR's Preserve and Education Manager), introduced me to an experienced archivist from Salisbury University, Ian Post. He created the Enduring Connections database which was specifically catered to researching African American genealogy on the Delmarva Peninsula.

For this project, I used Ian’s database, as well as digital copies of the Upshur Family Papers he acquired from the William & Mary University archives. These ledgers and handwritten notes recorded the purchase and hiring out of slaves at Brownsville. Hiring out slaves was a practice defined by an owner creating a (typically yearly) contract with another individual for their enslaved person to work elsewhere for a set fee.

This practice was common on the Eastern Shore. However, the amount of enslaved individuals that the Upshurs owned was atypical and demonstrated their wealth. As documented by author Kirk Mariner, by 1850 only a little over half of the white households of the Shore (55.8%) had slaves and of them ... 44% in Northampton owned five or fewer. While most Eastern Shore slaveholders owned a few individuals to conduct field work during productive seasons and then be hired out when expenses were too high, the Upshur’s owned approximately 113 individuals between 1782 and the time of Emancipation.

During the research process, I found evidence that reasserted my belief that the Great Migration never ended. African American historians know this process both professionally and personally. As I dived into the stories of the Black Upshurs, I thought of my family’s dispersal across the East Coast. I knew the core of my family was centered around the Shore, but I also had cousins in places like Philadelphia, Baltimore and Delaware. I knew my father was raised in Philly and my maternal grandmother lived in Baltimore until her 30s.

Both of them would visit their families “down South” for family reunions, funerals or when they needed to evade the struggles that befell them in their respective urban environments. I had done the same. When teaching during the pandemic became too overwhelming, I also moved back to the Shore. Instead of one-way movement North, there are pockets of Black prosperity that African Americans flock to. This story was true for me, just as it was true for the formerly enslaved African Americans of Brownsville as they sought opportunities after Emancipation.

Finding Connections in the Past

There were two Black individuals from Brownsville that I related to in their willingness to seek opportunities elsewhere. The first was Rachel Heath. She gave the most detailed account of Brownsville from an enslaved individual that I acquired during my research. The second was Neverson Upshur, who was also raised at Brownsville.

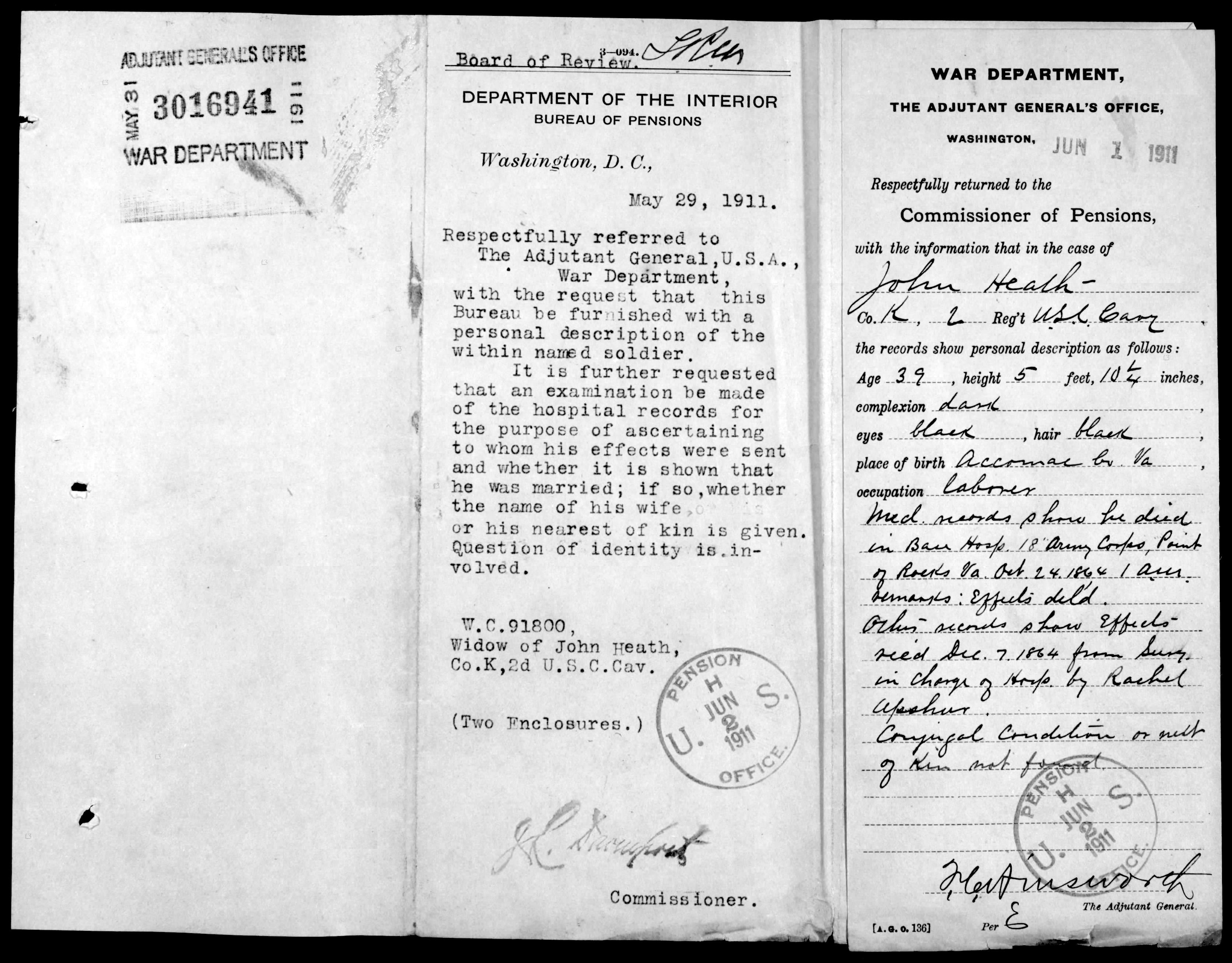

What I deciphered about Rachel’s life story became the launching pad that spurred future discoveries about the African American Upshur family during slavery and directly after Emancipation. Rachel was born in September 1826 to Nanny (or Ann) and an unknown father. She married John Heath, a free Black man of Accomack, VA in 1859 at Brownsville. Her pension deposition to receive benefits after John’s death was a monumental find, because her first hand account of the marriage offers insight into what life on Brownsville plantation may have been like during a period of increasing racial tensions throughout the country.

First, it showed that free African Americans had the ability to travel on the Eastern Shore. As stated by author Kirk Mariner, “Slaves who work in the field are physically unrestrained, fully capable of being dispatched up to the main house to retrieve a horse and carriage, or of running into the woods, even of venturing abroad to another plantation in hopes of recruiting a better master.”

Rachel and John likely met previously and probably in secret before their union. She detailed that the marriage took place on the plantation and that other enslaved individuals were in attendance, including John Adams and William Cooper who also later moved to Baltimore, MD. This suggests that Thomas Upshur, the owner of Brownsville at the time, overlooked personal ongoings among the enslaved on his property.

Second, it forced me to hypothesize that more African American Upshur descendants served in the Civil War. And my suspicions were correct—15 Black men with the surname Upshur hailing from the Eastern Shore of Virginia enlisted with Union forces and served in the Civil War! There was strong evidence through the ledgers and service documents that six of these men were from Brownsville—Henry, Arthur, George, Neverson, Smith and Samuel—all members of the 2nd Regiment U.S. Cavalry, Company K.

In 1880, Rachel was 60 years old and worked as a nurse in Baltimore, MD. Census records indicate that she was boarding with a family, James and Caroline Sowell and their three children, at that time. In 1911, Rachel died of unknown causes in Baltimore, but her journey from an enslaved girl on the Shore to a widowed nurse in Baltimore provided vital context to the experiences of all Brownsville’s Black descendants.

An Exercise in Patience

Engaging in genealogical research was an exercise in patience. Oftentimes, enslaved individuals disappeared from the historical record, a frustrating and common occurrence that was amplified by the scarcity of artifacts related to the enslaved.

Scattered within rows and rows of AncestryDNA digital records were hundreds of enslaved individuals with biblical names such as Leah, James, Benjamin, Issac and Hannah. Sometimes, I would learn that a person knew how to read, or left the Shore for a job opportunity up North, and then suddenly they’d just be… gone.

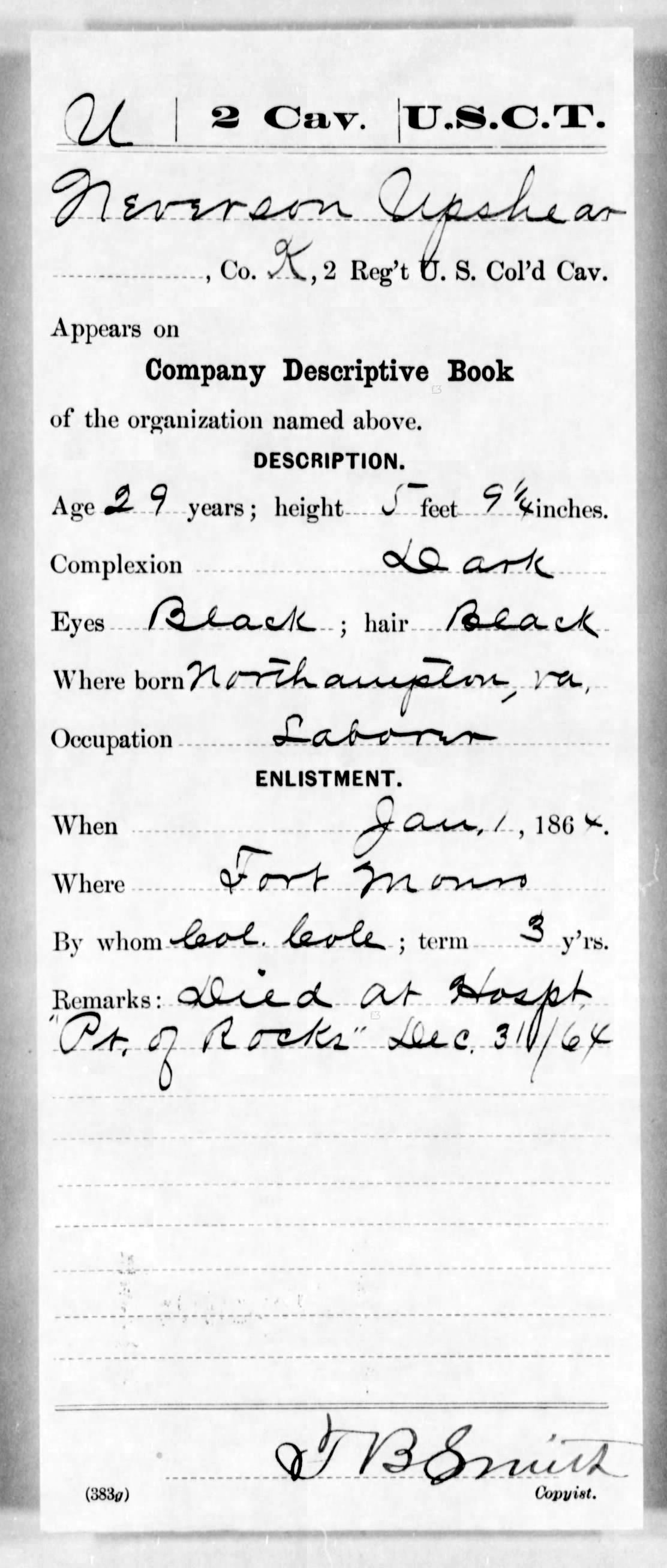

Enter: Neverson. His unique name was potentially a misspelling of Nevison but it stood out and allowed me to track his journey with confidence. Little is known about Neverson’s biological parents, but he was likely born on November 29, 1833. His mother Adah was approximately 27 years old when she gave birth to Neverson, but no details about her life or partner are listed in the Upshur Family ledgers.

When Union troops marched to farms on the lower Shore on January 1, 1864, Neverson and his brother Arthur enlisted in the 2nd Regiment U.S. Cavalry, Company K. Sadly, Neverson disappeared just as quickly as he was found. He fell sick on December 8, 1864 during the siege of Petersburg and Richmond. He died in the hospital at Point of Rocks, VA on December 31, 1864.

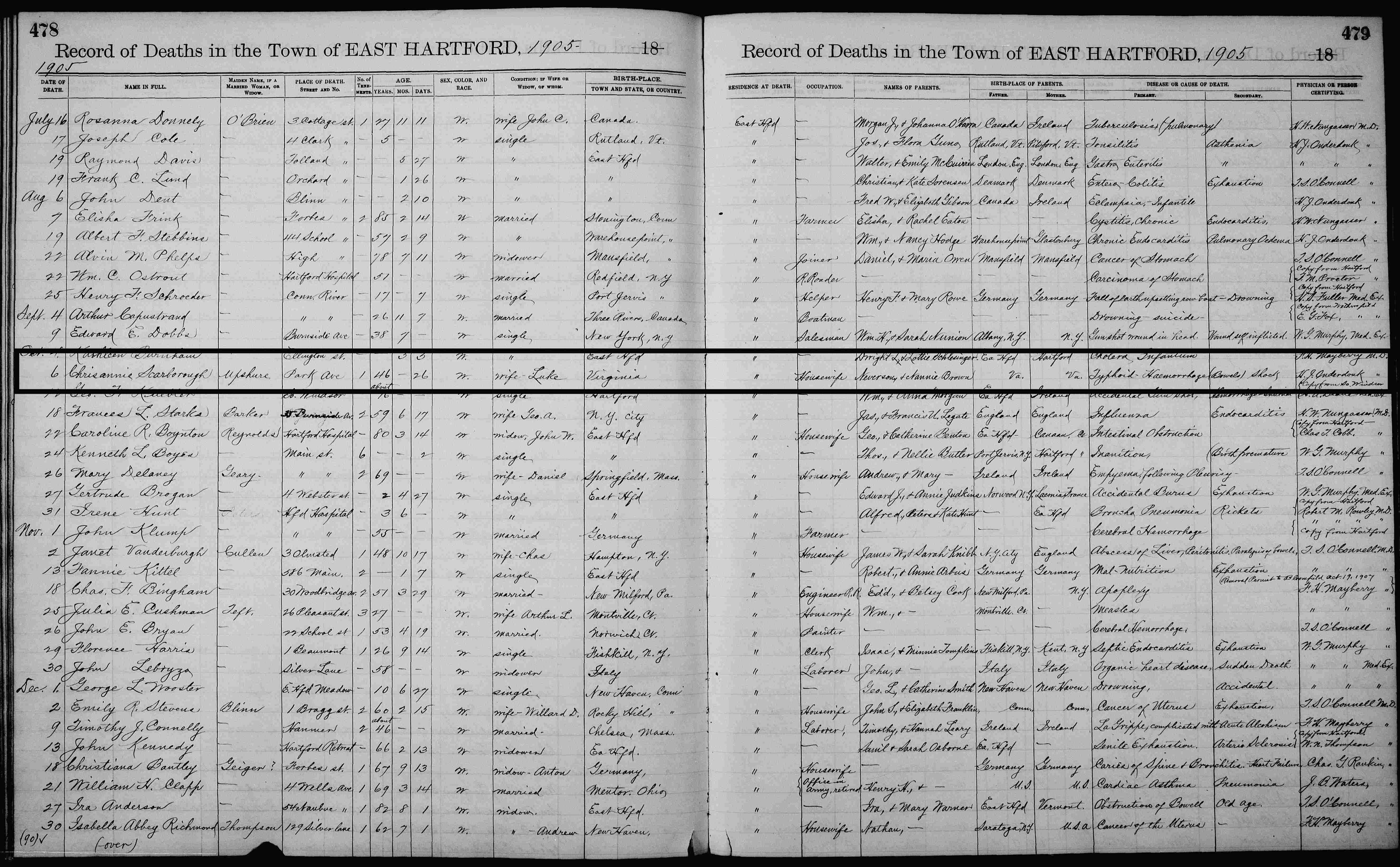

But, he left behind a daughter. She was named Chrisanna, after his sister. She survived Emancipation but what became of her mother listed as Nannie Brown is unknown. Chrisanna moved to East Hartford, Connecticut and by 1900 she was 40 years old, married to Luke Scarbrough and they shared five living children. She died in 1905 and was buried in the same community of East Hartford where many African American transplants from Virginia lived.

As I dived into the history of the Upshurs, I wanted to know more about my ancestors on the Shore. I felt a little naughty as I stole moments throughout the workday to enter the Moses surname into Ancestry.com. A seemingly small discovery created a rush of emotions. My eyes nearly popped out of my head as I read about one of my ancestors that had an occupation other than laborer listed on the 1850 Census. His name was Levin Moses, and he was a fisherman!

I nearly cried. I felt so connected to the Bay. I felt steeped in my roots; this was my story, my anchor. The significance and similarities to my recent experiences were uncanny. I too work on the Bay. As a field educator for the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, I spend most of my days on a jet boat, talking to students about the history of this region, marine organisms and their importance and the current consequences of pollution and climate change.

Quote

I nearly cried. I felt so connected to the Bay. I felt steeped in my roots; this was my story, my anchor.

When European explorers “discovered” the Chesapeake Bay, oysters were so plentiful that they jutted out of the water like pillars, and ships could run aground on them. For generations, Black individuals were oystermen, longshoremen and sailors, but their roles in these industries were overlooked then and are forgotten today.

My thoughts raced as I contemplated my ancestor’s life. Was he actually a sailor or did the census writer feel lazy that day and didn’t write longshoreman? Could he swim? Was he a fisherman, a crabber, an oysterman or a deckhand?

I imagined that he couldn’t swim, like so many sailors at that time and unfortunately the same fate of many Eastern Shore residents today. Each day must have been arduous, but maybe he experienced the same sort of excitement I feel on the water. A sense of marvel at the steady waves and the beaming sun, a sense of adventure with the prospect of entering a new port, a reassurance that the next day won’t be the same as the last, a submission to the weather and the tides.

Quote

His name was Levin Moses, and he was a fisherman! Each day must have been arduous, but maybe he experienced the same sort of excitement I feel on the water. A sense of marvel... a sense of adventure.

Reflecting on the Past

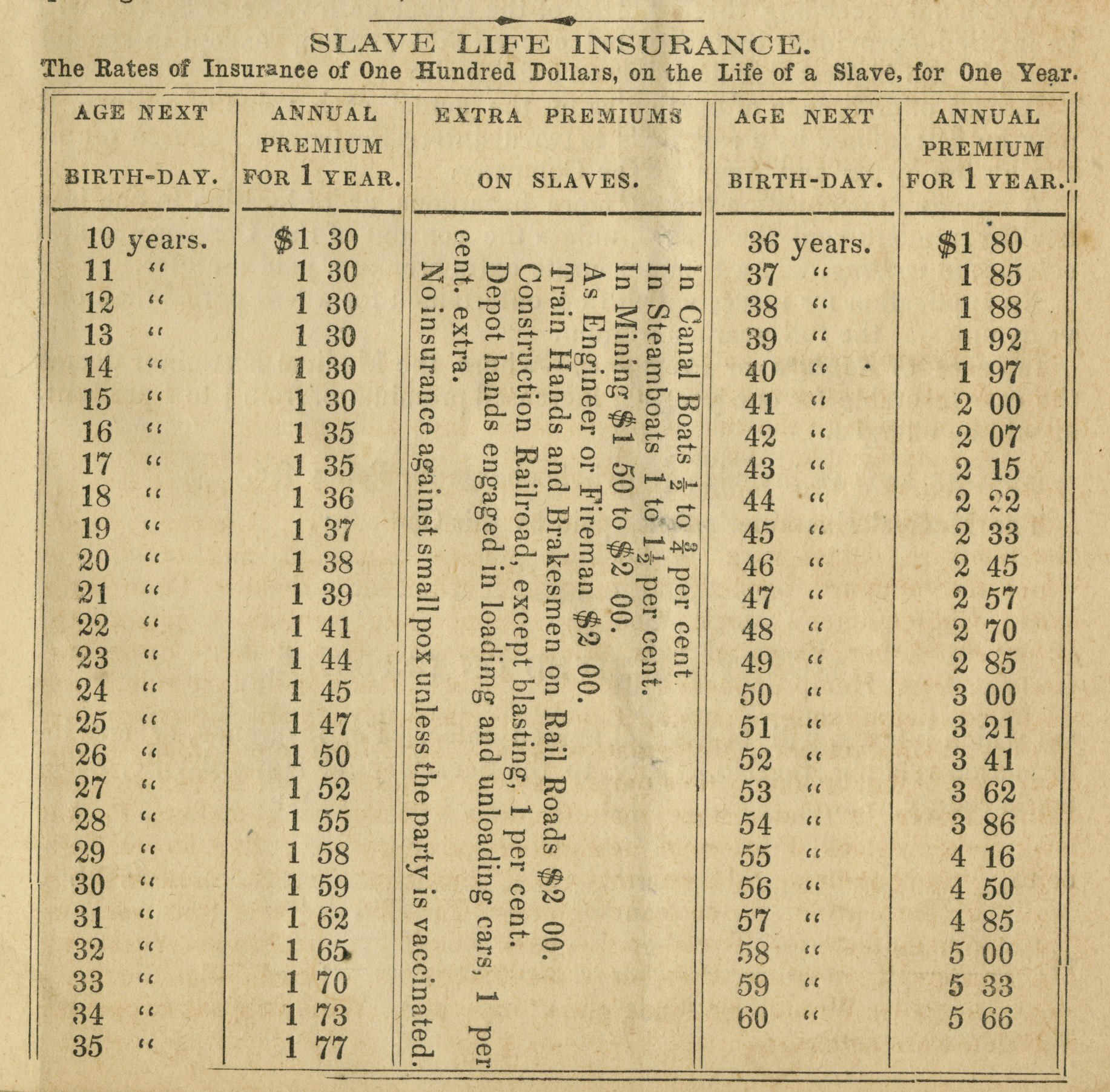

When I took on the role of historical researcher, I had to constantly remind myself not to dwell on the harsh realities of the past. Seeing human beings listed on tax documents sent jolts through my system. If we were owned, were we insured? The answer is yes. Were we just depreciating assets? The process of hiring out slaves also arose often in the historical record, and the thought of individuals being rentable chattel was equally disheartening. I constantly thwarted overwhelming sympathy and paused to remind myself, “That was then, what am I going to do now?”

However, as I found more, I reflected more. I became curious about my own heritage and I sought to understand why this work was important for environmentalists. Each week, discoveries such as a marriage certificate or a Census document became treasured finds. Finding out that an African American descendant from Brownsville could read was so comforting, even though I knew these people were not my kin.

To go on an archival journey from enslavement to literacy then proceeding to property ownership merely by finding pieces of paper was indescribable. I experienced joy when someone moved North for a new start, and sadness when they disappeared without a satisfying or succinct explanation. I experienced guilty pleasure moments when I flipped through Census records to see what my own family was up to in 1860. I felt like a detective when I investigated historical documents and speculated what events caused Black Upshur descendants to move or separate.

All of these discoveries were valuable because they demonstrated the interdisciplinary nature of conservation and historical preservation. The lives of the Black Upshurs were key to forming the landscape of Brownsville, and the archaeological evidence that remains is at risk from being swept away by the Atlantic Ocean due to climate change. Projects like this one are unconventional but innovative and necessary as documentation efforts are critical for areas that are threatened by heightened sea levels, erosion and other forms of ecological degradation. Historical research projects offer understanding and connection to the past when an ever so shaky future lies ahead.

We Can’t Save Nature Without You

Sign up to receive monthly conservation news and updates from Virginia. Get a preview of Virginia's Nature News email