Tennessee Caves (and the Bats That Use Them)

Twenty percent of known caves in the United States are located in Tennessee.

Twenty percent of known caves in the United States (10,000+) are located in Tennessee. In additon to numerous species of bats, these caves harbor hundreds of vulnerable species—mostly crustaceans, insects and arachnids—that live exclusively in these subterranean habitats scattered throughout much of the lower 48 states.

Protecting Cave Ecosystems

Preserving cave ecosystems represents one of The Nature Conservancy’s highest priorities in Tennessee, for good reason. Little is known about the animals living in these complex, subterranean landscapes.

Additionally, caves contain critical habitats that connect fields and forests above ground with groundwater below. Subterranean ecosystems depend on water and debris entering from sinkholes and other entrances to nourish cave-dwelling species and also animals—like bats—that regularly come and go to feed. Alterations to the landscape and water table surrounding a cave, or complex of caves, directly affects the delicate balance required to maintain the health of these rich ecosystems.

Tennessee's Bats

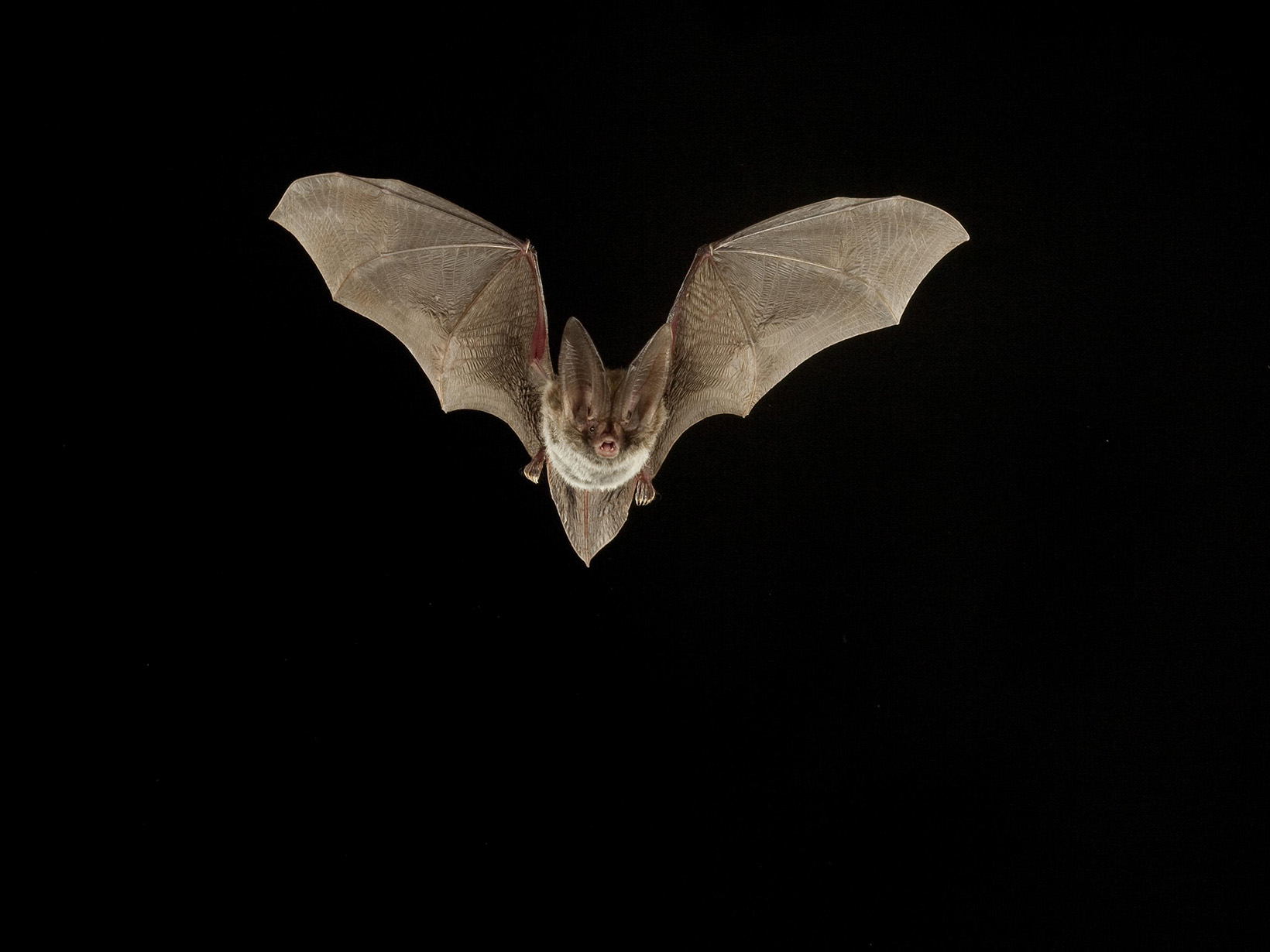

Tennessee’s best known cave dwellers are bats, including gray bats and Indiana bats which are both listed as federally endangered. Depending on the species, bats use caves for hibernation, maternity and as a respite during migration, forming colonies numbering in the thousands and sometimes the hundreds of thousands.

Bats are especially sensitive to disturbances in caves. Waking bats during winter hibernation causes them to use energy stored to survive the season. Disturbances during summer threaten young bats in maternity colonies that have yet to take flight.

More recently, an epidemic called white-nose syndrome (WNS) has devastated bat populations in the eastern United States and Canada. The culprit, an invasive fungus called Pseudogymnoascus destructans (Pd.), damages the wings of cave-dwelling bats. Infected bats wake more frequently during hibernation and exhaust critical stores of fat required to survive the winter. Most caves where the fungus has appeared have resulted in bat die-offs of up to 90%. In response, TNC works with partners to monitor bat populations and evidence of WNS in caves across Tennessee, and shares data to inform treatment of this disease.

Quote: Gabby Lynch

Our subterranean work has expanded into collaborating with partners to study and understand some of the greatest challenges in caves and karst conservation, including white-nose syndrome and bat migrations.

Build a Bat House

Building a home for bats can provide shelter that plays a vital role in their survival. Although bats often go unnoticed, they are the top predator for night-flying insects, so having them around helps with controlling the insect populations for farms, gardens and forests. Learn how to provide a shelter for Tennessee bats.

Cutting Edge Tools

In an effort to learn more about bat behavior in Tennessee, TNC scientists are working with a variety of partners to better understand the state's bat populations and behaviors. For example, TNC became the first organization to apply a new generation of radio transmitters that are small and light enough to adhere to bats, but large enough to be detected by Tennessee's growing Motus Wildlife Tracking System, an international network of stationary towers that use radio telemetry to track and share data about migrating species.

Tennessee Caves and Karsts

Leading the Way

The Nature Conservancy has been conserving Tennessee caves since 1978.

Purchased Hubbard’s Cave, a premier bat cave in the Southeast, and built the largest cave gate in the world to protect gray bats. (Since then, TNC has built 34 cave gates, with two more expected in 2020.)

Convened with partners to develop a list of Tennessee caves in most need of protection.

Performed the first comprehensive biological inventory of a Tennessee cave, with assistance from local recreational cavers, to reveal overwhelming biodiversity and establish the subterranean world as a new conservation frontier in the region.

Co-founded the Tennessee Bat Working Group, a coalition dedicated to sharing information between academia, land managers and the public.

Acquired Pearson and Bellamy caves, which in addition to Hubbard’s Cave, account for the majority of gray bat breeding and hibernation habitat in Tennessee.

Helped create and test new thermal video technology that improves the ability to understand gray bat populations and behavior.

Facilitated a working group to create a management plan for Chiquibul Cave in Belize—Central America’s largest cave system.

Constructed the world’s first artificial cave specifically designed for hibernating bats.

Initiated a shared network of towers featuring technology that gathers information on aerial wildlife, including bats. Worked with The Conservation Fund to acquire priority Indiana bat habitat in East Tennessee.

Together with partners, TNC completed a second cave gate at Piper Cave. This multi-year restoration project involved removing 320 cubic yards of trash and aiding in rewilding efforts that have exceeded expectations.