The Sound of Success

Listening to the birds to measure forest health in the wilds of Maine.

On a warm July day in the remote northwest corner of Maine, very near the Canadian border, Nancy Sferra swats at mosquitos with one hand while nimbly using the other to detach a small boxlike device from a tree. The unit, about 6 inches square, is a dull green color—designed to blend into the surrounding forest.

Sferra and her team aren't collecting biological samples or even pictures—they're capturing sounds.

"We've got three of these out here about a quarter to half a mile from each other," explains Sferra, The Nature Conservancy in Maine's director of stewardship and ecological management. "I'm looking forward to hearing what we've got."

Birds in the Sugar Bush

The project started when TNC decided to open a portion of their St. John River Forest to a sugar bush lease. The sugar bush—another term for a stand of maple trees grown for maple sugar production—is a way to retain mature forest habitat for warblers and other birds while generating revenue and a sweet and sustainable forest product.

"The priority for us has always been to maximize the forest's ecological benefits in the long term," continues Sferra. "And a healthy hardwood forest with plenty of underbrush is ideal habitat for songbirds."

And what better way to find songbirds than by listening for their songs?

Recording Sounds to Monitor Birds

In 2016, prior to tapping any maple trees for syrup, the team established a baseline using a point count technique: they selected spots in the forest and listened for birds within 50 to 100 meters from each position during time intervals lasting ten minutes each. Using this method, they identified the most common species and the frequency of each bird's presence.

Now, technology provides a helping hand. The devices Sferra is collecting are called song meters. They are compact, weatherproof, acoustic recorders capable of longterm sound monitoring of frogs, insects and birds. The high-quality stereo microphones can be programmed to record at any time of day or night.

"We set these to record for two hours starting a half hour before sunrise and two hours before sunset," says Sferra. "Many bird species are generally active and vocal early and late in the day. Our home base is a long way from the St. John River Forest, so this 'set it and forget it' technology is a huge boost to our ability to monitor the forest."

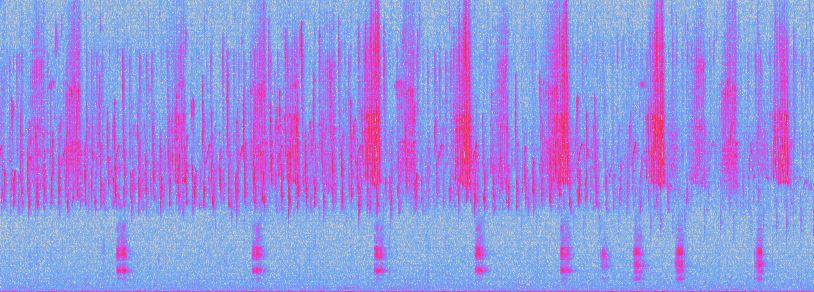

The song meters were originally put in place on May 21 and have regularly recorded twice a day until July 1, when they were removed. That's a lot of recordings to listen to—more than 160 hours worth! To help identify species on all those recordings, Sferra uses software to create a spectrogram: a visual representation of the spectrum of frequencies. Many bird songs, woodpeckers drumming, and other forest sounds are readily identifiable by their spectrogram signature.

"There are a whole lot of ovenbirds out there right now. You can see the heavy blocks made by their really loud, compact calls all over the place on the spectrogram," Sferra notes.

St. John River Forest Spectrogram Recording

How many birds can you identify?

Sounds Tell the Story of Forest Health

TNC's science team will use the spectrograms to compare the relative abundance of species with the prior baseline data. An example of a species of interest is the black-throated blue warbler. Because these small birds like to nest in underbrush vegetation like hobblebush, they can act as a kind of bellwether species indicating a healthy hardwood forest with a diversity of structure, particularly in the understory.

And it's not just birds that reveal themselves through sound. So far, clomping, snorting moose, and cackling coyotes have been heard on the recordings. One unit was pried open by what, judging by the claw marks, appears to have been a curious bear. The SD card is undamaged and the team is looking forward to hearing whether the event was captured on the recorder!

Twenty Years of Innovative Forest Management in the St. John

This effort is part of innovative forest management that TNC has been employing in the St. John valley for twenty years. In December 1998, The Nature Conservancy purchased 185,000 acres, including 35 miles of frontage on the upper St. John River. This acquisition, the largest by TNC anywhere in the U.S. at the time, changed the way much of the conservation community approaches land protection. A massive fundraising effort in just six weeks proved that a dedicated group of caring, resourceful and generous people can accomplish conservation at a scale never thought possible before.

Over the years, TNC scientists have made findings in the St. John River Forest that confirm the wisdom of that bold investment: previously unknown populations of rare plants, sightings of Canada lynx with kittens, and ponds with full complements of native minnow populations. Other discoveries include the largest population of purple false-oats in the United States, stands of black spruce over 300 years old, and a dozen rare dragonfly species.

Using Carbon Storage to Fund Conservation

About 80,000 acres of the St. John River Forest property is now designated as reserve land, where natural processes are uninterrupted by human management. Set aside for conservation and study of Maine’s ecosystems, reserve land provides important information about how old growth forests respond to natural challenges and support wildlife species. And big, old trees hold a lot of carbon.

Recently, TNC has enrolled a significant portion of the St. John River Forest in a forest carbon storage project. This involves a long-term commitment by TNC to increase carbon stocking, accelerate the restoration of the forest, and increase the acreage dedicated to ecological reserves. The project includes portions of reserve and sustainably-harvested lands, and all of the sugar bush.

"We're demonstrating that well-managed forests can meet critical ecological objectives while providing a source of revenue to be invested in future conservation opportunities," says Bill Patterson, senior field representative for northern Maine. "It's a win-win for nature and people."

Nancy Sferra and her stewardship team intend to keep it that way.

"We'll continue monitoring as the sugarbush operation matures to ensure that this habitat maintains its ability to support a diversity of life," says Sferra. "If something changes in that forest, we'll hear about it."