Restoring Reefs to Build Resilience

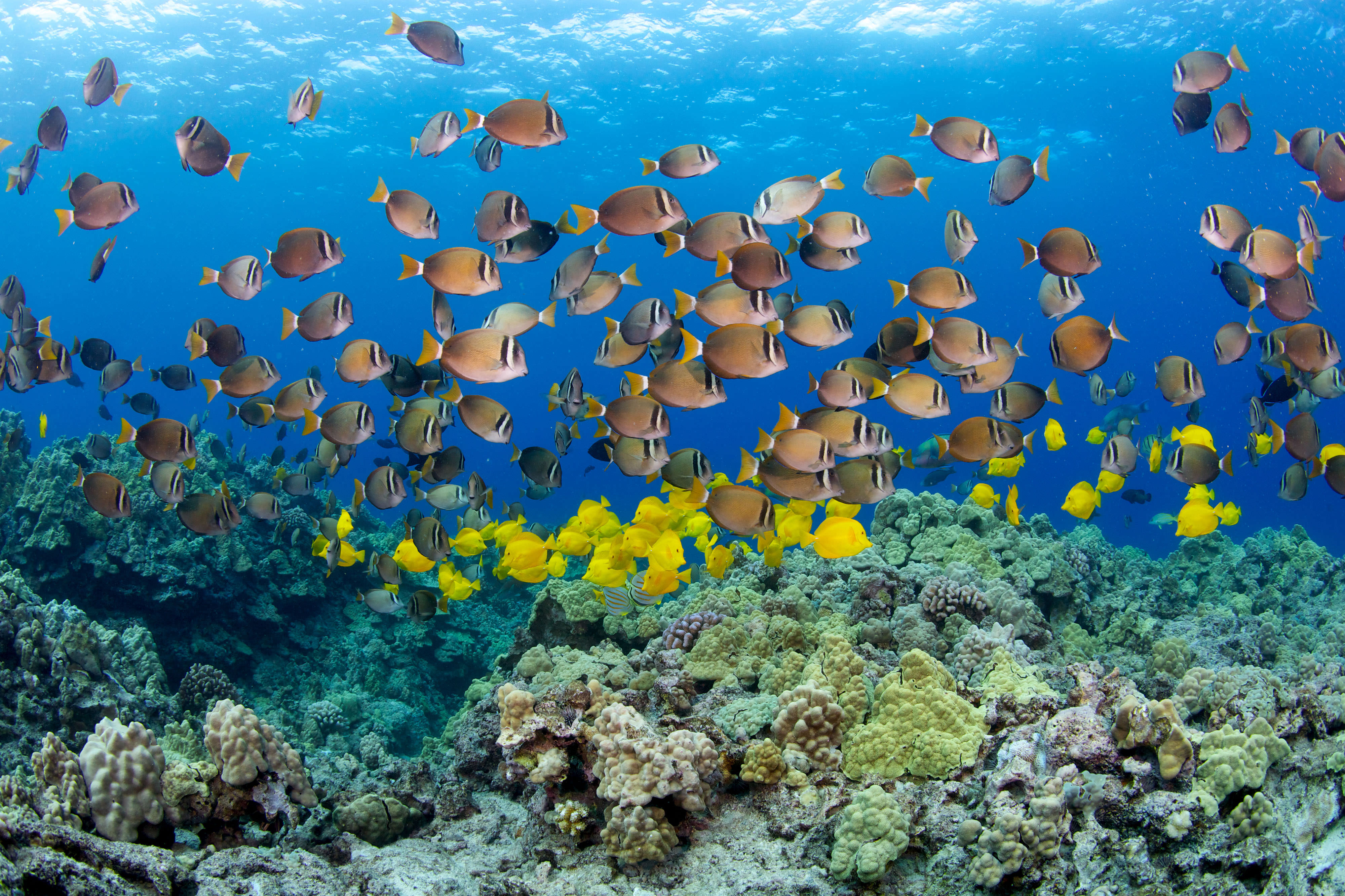

Coral reefs are living ecosystems that protect and provide for about 25% of all marine species—and for all of us.

Reefs in Hawai‘i

Hawai‘i's Reef Inhabitants

These massive living structures are vital to Hawai‘i’s people, culture, lifestyle and economy, providing more than $2 billion each year in flood protection and reef-related tourism alone.

But reefs are under increasing pressure from sediments, land-based pollutants, overfishing and climate change impacts, including rising sea levels and water temperatures, which are expected to intensify in coming years.

Scientists estimate that live coral cover in at least some areas of Hawai‘i has declined by 60% over the past several decades. Reducing the impacts of local and global threats is critical to the survival of coral reefs.

Reef restoration has been helping to regenerate reefs in other parts of the world for more than two decades. With recent bleaching events resulting in a 30% loss of live coral cover in Hawai‘i, it is essential to understand the potential of this intervention to sustain Hawaiʻi’s spectacular coral reef ecosystems and the many benefits reefs provide.

Read about how coral bleaching impacts reefs.

Reef Restoration

Reef restoration is the process of rebuilding or enhancing damaged or degraded coral reefs to improve their health, function and/or resilience. This can involve a variety of techniques, including coral stabilization and coral gardening. These methods aim to increase coral cover and diversity and enhance the overall resilience of the reef ecosystem.

Prior to any reef restoration, it is essential to reduce threats on the reef that may be causing degradation and coral mortality. Improving the overall health and resilience of the reef increases the chances that planted coral will survive and thrive.

We typically reduce threats by improving conditions in the ocean and surrounding areas, for example, by promoting sustainable use of marine resources and by reducing land-based sources of pollution to improve water quality.

Reef Restoration in Hawai'i

TNC’s marine scientists are working with federal, state and community partners to develop a gold-standard for science-based, adaptive and community-centric restoration in Hawai‘i. Together, we are piloting reef restoration at sites where corals have been lost but where the reefs have proven to be resilient—meaning the corals resisted or are recovering from climate-related bleaching—and where communities and government partners are implementing complementary efforts to reduce reef-damaging threats and improve reef health.

We are working in close collaboration with community partners, who selected the pilot project locations, coral species and restoration techniques that will be used in consultation with restoration scientists.

We recover and use only those corals that have been broken during recent storms or high swells and would otherwise die. To minimize the risk of introducing disease or invasive species from other places, our teams only replant corals near where they were recovered.

Target species for Reef Restoration

“He pūko‘a kani ‘āina”

“A coral reef that grows into an island”

ʻŌlelo Noʻeau (Hawaiian proverb)

Pilot Sites

Pilot Sites

The Nature Conservancy worked with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Hawai‘i Division of Aquatic Resources and University of Hawai‘i Institute of Marine Biology to develop a Coral Restoration Action Plan for the state. The plan identified priority geographic areas for restoration, and we are now collaborating with community groups and other partners to pilot reef restoration at three of these sites.

Olowalu, Maui

The Olowalu reef is a source of coral larvae—a “mother” reef—for other reefs in West Maui, Moloka‘i and Lāna‘i. We are working with scientists from Stanford University and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute and local partners to assess the thermal tolerance of coral and the hydrodynamics of the area and determine optimal reef sites and coral species for reef restoration. Read more about efforts to protect this valuable reef.

Kealakekua, Hawai‘i Island

Growing numbers of visitors to Kealakekua in recent decades are taking a toll on the area’s natural and cultural resources. Hoʻāla Kealakekua Nui is working to prevent further degradation and partnered with TNC and Hawai‘i’s Division of Aquatic Resources to launch Kanu Koʻa, a pilot restoration project to accelerate coral growth and reef recovery in the bay, one of only 11 Marine Life Conservation Districts across the state. See photos from the project launch.

Ka‘ūpūlehu, Hawai‘i Island

The 2015 coral bleaching event took a devastating toll on the area’s reefs. To accelerate reef recovery, we launched Kanu Ko‘a, a pilot restoration project, in close collaboration with the Ka‘ūpūlehu Marine Life Advisory Committee. For nearly three decades, this group has been working to restore health and abundance to the waters of Ka‘ūpūlehu, so the reefs and the fish that rely on them can continue to provide for the community and future generations. Read more about the efforts to protect the cultural traditions and natural resources of this wahi pana.

Emergency Repair

Reefs protect our shorelines by breaking down wave energy.

Hurricanes are a threat to coral reefs because they can do a lot of structural damage very quickly. Research shows that one severe hurricane can cause a 50% or more loss of live coral cover—and the loss of just one meter of reef height could double the cost of storm damage on coastal properties and infrastructure, such as roads and sewage systems.

TNC purchased an insurance policy covering reefs across the Main Hawaiian Islands against hurricane and tropical storm damage. Pre-determined payouts from the policy, based on windspeed in the covered area, can be made within days, providing funding to expedite essential reef repair activities such as debris removal and coral re-attachment.

We convened scientists and reef managers from government agencies, universities, local non-profits, community groups and other organizations to share restoration techniques and develop a statewide rapid response protocol. We also worked with local teams to develop response plans for each county to ensure an effective post-storm response.

Reflecting global restoration expertise and lessons learned from post-storm repair on the Mesoamerican reef, these efforts will facilitate coral regrowth after a damaging event to build reef resilience.

Monitoring Outcomes

Using new technologies, we are able to stitch hundreds of overlapping photos together to create 3D models of the reef. The photos can then be analyzed by computer, reducing the need for highly trained research divers.

TNC’s reef repair and restoration activities complement other actions we take to reduce local pressures on reefs and fisheries, so they are productive and abundant long in the future. Learn more about what we do.

Make a Difference in Hawai‘i

The Nature Conservancy works with people like you to protect Hawai'i’s spectacular diversity of life. Together, we can protect the plants and animals that share our world and support our well-being. We invite you to join the effort.

We Can’t Save Nature Without You

Sign up to receive monthly conservation news and updates from Hawai’i & Palmyra. Get a preview of Hawai’i & Palmyra’s Nature News email.